The Apprentice of Fugue, on piano

February 12, 2024

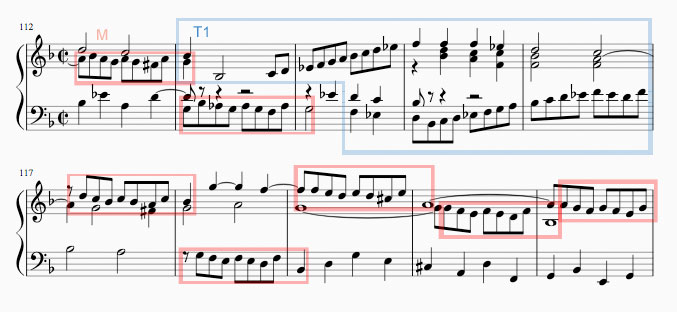

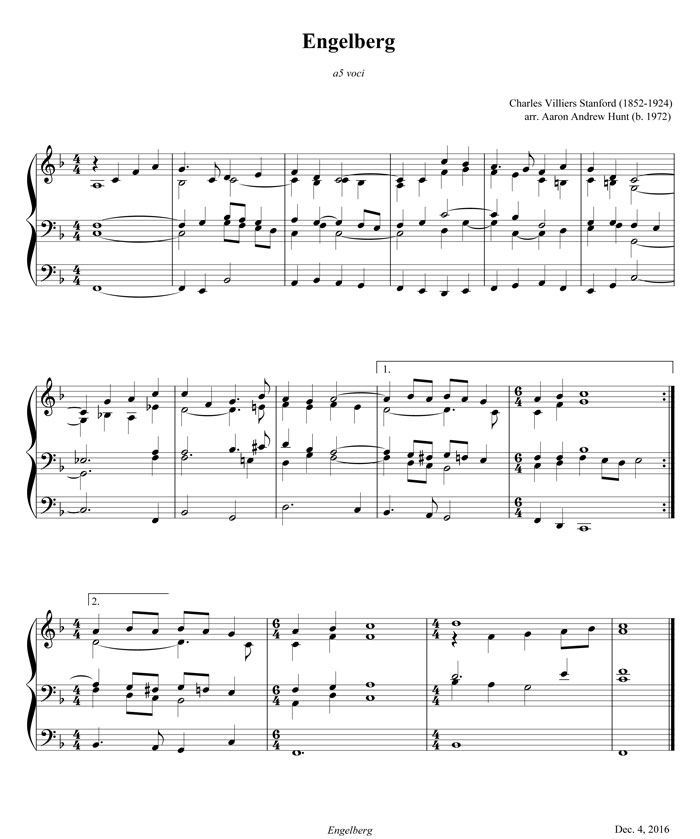

Some of you might already know that I released a new album on February 4, 2024 — a performance of The Apprentice of Fugue played on piano (a Steinway D concert grand). The music was written in 2022, and that year I had released a recording on organ under the original title of the work in German, Der Lehrling der Fuga.

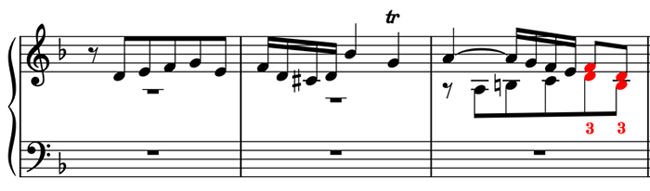

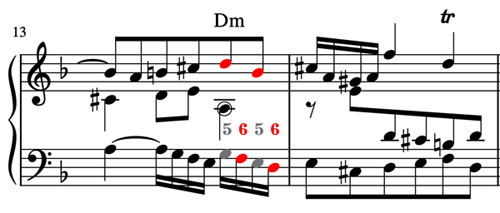

To celebrate this release, my friend Stephen Malinowski made animation videos for Contrapunctus 11 and Contrapunctus 3. As many of you know, Stephen has an uncanny ability to match music to visual patterns. He also knows Bach's music very well, and has an excellent understanding of counterpoint and composition, so he had no trouble at all getting into the inner workings of these pieces. We corresponded over a period of several weeks, during which time Stephen tweaked the visuals again and again. I hope you'll take some time to appreciate the great attention to detail taken in these videos. In Contrapunctus 3, the chromatic lines are rendered with something that looks a bit like the eddies of a small fish swimming in clear water, which fits the feeling of the counterpoint perfectly.

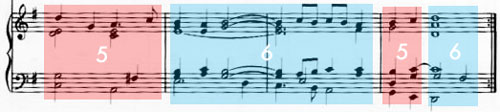

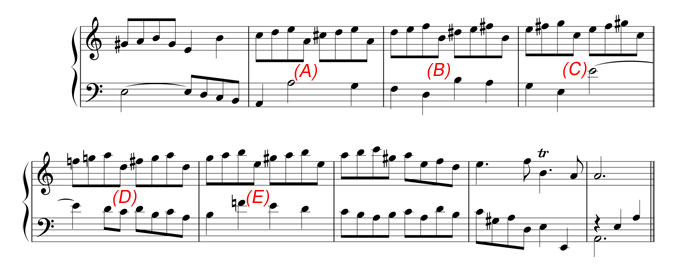

In Contrapunctus 11, there are three subjects, which are the same three subjects used in (my) Contrapunctus 8, but inverted (turned upside-down). Whereas Contrapunctus 8 has three voices, Contrapunctus 11 has four; as in Bach's original, the fourth voice often verges on becoming a fourth subject – a stepwise line, usually chromatic. Bach used repeated notes in his third subject to give a feeling of insistence and urgency. One of my goals throughout this project was to avoid simply copying whatever Bach did. Rather, I wanted to to come up with my own way of doing something similar which might have a chance of being as successful (which I consider a healthy view of tonal composition in general). So I use the notes of his main theme, but (importantly!) I change the meter and rhythm. All other subjects (apart from the BACH subject in the closing fugue) must use different notes. For that reason, my third subject in Contrapunctus 11 doesn't use repeated notes — at least not directly. Instead, neighbour-tones are used. Stephen rendered this subject with spiralling thread-like patterns that fit the contour of the subject perfectly. Bach's second subject begins with a long note on the downbeat, and his third (repeated-note) subject begins with a weak-beat accented note that's often held over a barline (we can call this a "syncopation") — an exciting effect which produces expectation. I turned that around, using syncopation at the outset of my second subject, which allowed me to sometimes approach the third subject using syncopation, in such a way that the listener can't be sure which subject is going to follow that first note. That uncertainty lends an edge to the development. I discussed this with Stephen, and in the video you'll see that those syncopated notes are larger than the others, circled, and they rotate as a sort of "handoff" to what follows. It's these kinds of details that make these videos so much fun to watch!

If you like, you can also watch the corresponding "inversion" of the above triple-fugue in a video of Contrapunctus 8 Stephen made of the first recording of Der Lehrling der Fuga (played on organ, released in 2022).

Stephen also previously made a video of Contrapunctus 9 (which features double counterpoint at the 12th) …

… and Contrapunctus 1, which is among the least similar formally to any of Bach's original fugues, because (as you can read in the liner notes of the recording, or in the score) The Apprentice of Fugue also tells a story, which begins with PART 1 as follows:

"In order to make the masterpiece undoubtedly different, the apprentice looks for alternatives – including potentially clumsy combinations which the master had not used."

Needless to say, I would have never been able to write an Apprentice of Fugue were it not for Bach's Art of Fugue. Which touches on the reason I took on this project to begin with: to learn things I simply couldn't have otherwise learned. There's more to say about that, but I'll end here for now. In any case there will certainly be more episodes of Passages That Bother Me, so stay tuned!

Until then, I remain,

— AAH

Re: Passages that bother me BWV 552a (St. Anne, Prelude)

July 22, 2023

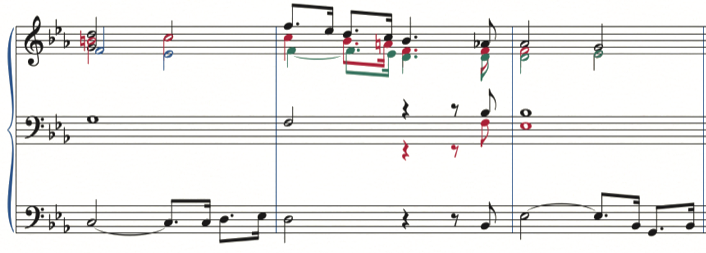

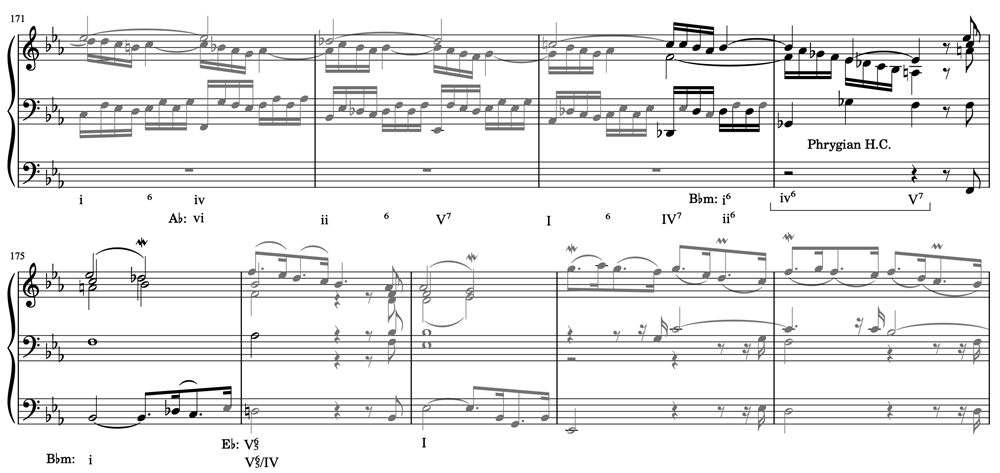

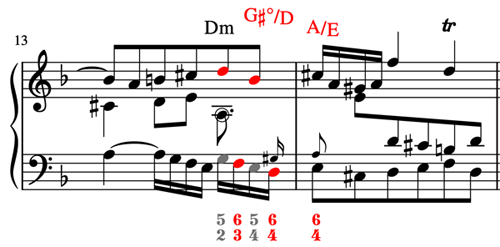

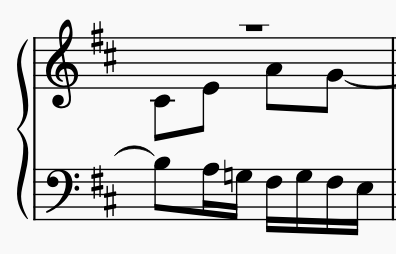

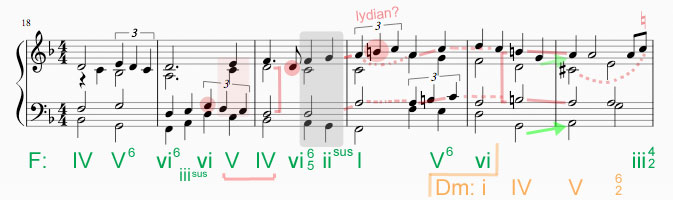

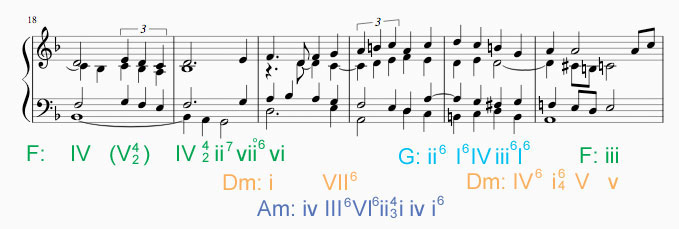

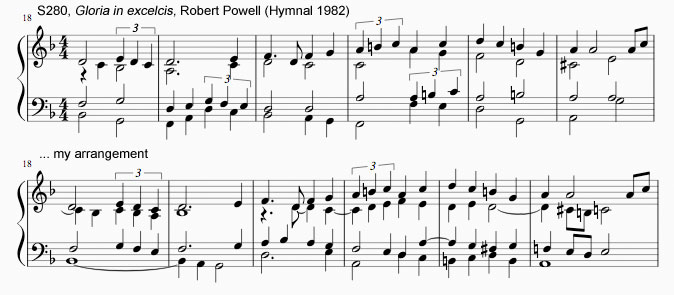

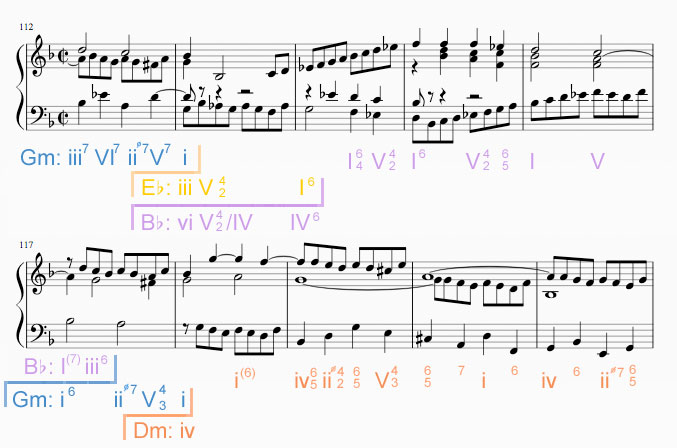

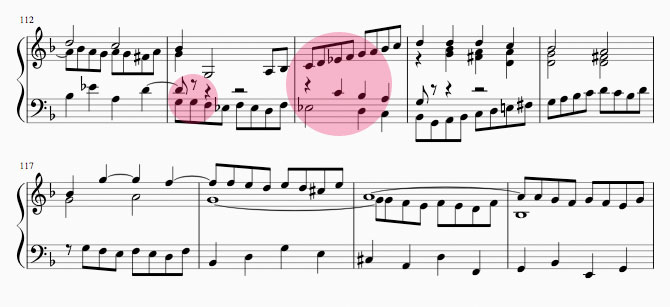

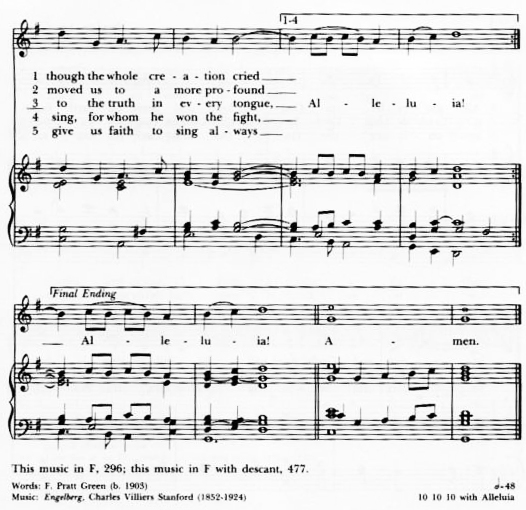

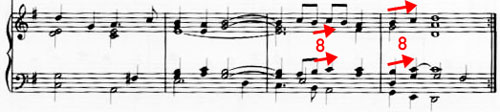

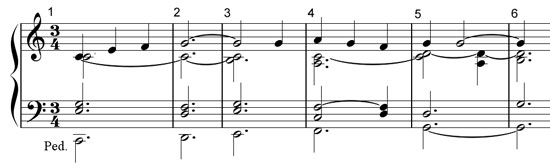

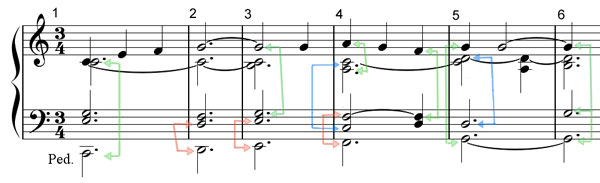

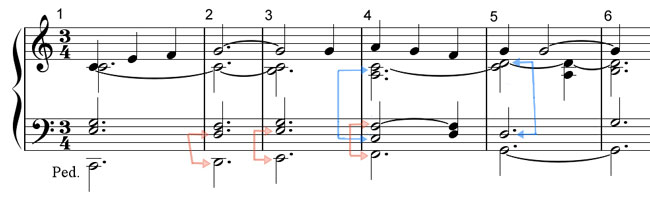

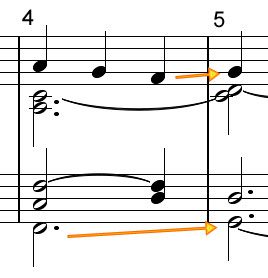

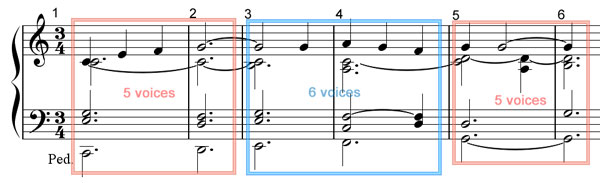

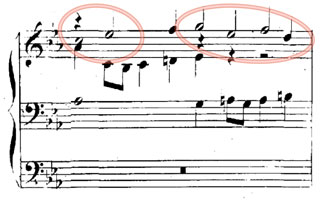

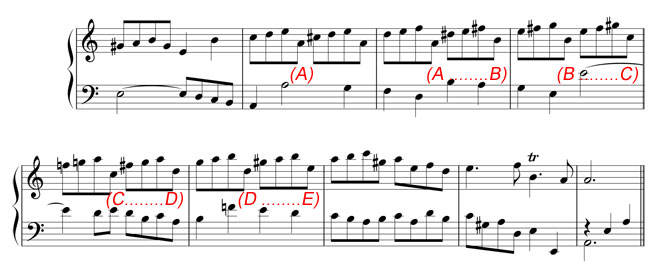

This is a short followup to our previous episode in the series "Passages that bother me", where I thoroughly scrutinised a questionable transition found in the great St. Anne Prelude which opens Bach's Clavierübung III, published 1739. We begin by citing the passage in question as Bach wrote it. The transition in question is between bars 175 and 176.

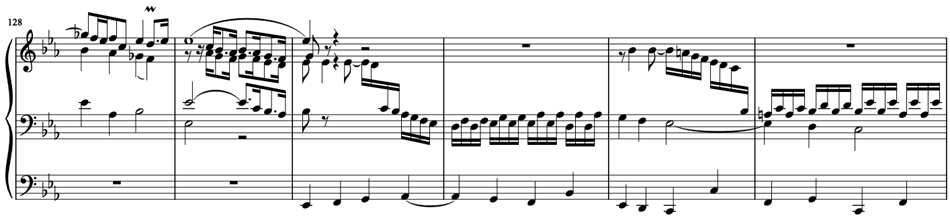

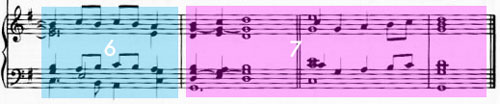

After publishing my investigations, which contained many possible approaches meant to possibly "improve" the above transition, I received a remarkable alternative which hadn't occurred to me, written by the esteemed composer Stéphane Delplace. A brief exchange of observations led to the following "final version".

The core idea of this alternative is to replace the B-Flat triad in first inversion with a D minor triad in root position. It's difficult to convey just how much wisdom is contained within this surprisingly simple idea.

Recall that a B-flat triad is the most distant diatonic relation to be found in C-Minor, and this fact is in large part responsible for giving the transition an awkward effect. When we replace this harmony with D-minor 7th chord, the majority of the awkwardness is removed in one stroke, since a very distant harmonic relation is replaced with a very close one. When the fifth is present, the chord is an altered harmony in the key of C minor, since the 6th degree must be raised from A-flat to A, but Bach's voice-leading suggests that the fifth shouldn't immediately appear; rather, it should "sneak in" almost unnoticeably. This note, A, then acts as a leading tone to B-flat, so that the voice-leading is finally as smooth as it should be. Because the C is now held as a common tone, the similar motion is decreased just enough that it no longer draws any undue attention to itself.

As an added benefit, this sonority on D minor contains not only a 7th, but also a 9th, namely the small 9th E-flat above the root D. Here is where a deep knowledge of Bach's harmonic language helps to understand why using this specific chord as the solution might just qualify as a stroke of genius! Because this specific chord, a minor triad with a minor 7th and minor 9th, turns out to be one of the most important aspects of Bach's harmonic language. I almost want to say something like "the best kept secret" of his harmonic language, because it seems few people have taken notice of Bach's consistent use of this specific harmony throughout his work. Precisely this sonority occurs as a ninth chord in the major mode, on the third degree, iii9. In minor, it appears here as an altered ii9, where the perfect 5th in the chord is the raised 6th of the minor mode, which is exactly what we see here in the above solution.

In fact, Stéphane Delplace has written a treatise on this very subject, this sonority and the special role it plays in Bach's music, which may be one of the most important treatises on harmony in the modern age. To everyone who wants to understand Bach's harmony, please go now and read this treatise. It is available directly from Delplace's website both in the original French, and in an English translation (which I had the honour of helping with).

III V § I C A (MUSICA, a treatise on harmony by Stéphane Delplace)

As a final note, I also came up with my own version using this same approach, to address a few things about the above solution which still bothered me. First, I found that the B-flat appearing already on beat 2 in the alto was too early, and the arrival should instead be saved for the descent of the soprano. Second, the full triad in three sustained parts on beat 3 seemed to stray unnecessarily from the original which sounds only the single note B-flat at that point. Lastly, the chords in the right hand require an awkward "hopping" motion if they are to be played by one hand, which I found counter to Bach's normal fluid style (although it is easy enough to play the passage by taking the second alto with the left hand, which is how I played it for the above recording). My version resolves these issues by introducing the fifth (A) as a quarter note on the second beat and resolving it on beat 3, resolving the second soprano to a unison with the first soprano, and dropping out the alto on beat four. The result is as follows.

Upon comparing these, I have to admit that, despite my objections, Delplace's version sounds smoother. The reason is that it contains no distracting elements, whereas the accented A in my version makes the ii9 stand out. Therefore I consider Delplace's version to be better. Which do you prefer? As always, I'm curious to hear what you think. Whatever you do, be sure to get the treatise! It has the potential to help you appreciate Bach's music on a new level, and radically change the way you think about harmony in your own work.

Peace,

Aaron

Passages that bother me: BWV 552a (St. Anne, Prelude)

May 15, 2023

Today I welcome you to another episode in the series "Passages that bother me". It's very rare that I have the feeling that anything should be changed in a piece by Bach, but loyal readers of this blog will know that I've written about an example or two in the past. This time it's the Präludium pro Organo pleno, from BWV 552, the great St. Anne Prelude and Fugue which is found at the opening of Bach's Clavierübung III, published 1739, which contains a passage that bothers me.

The Structure of the Prelude

In some ways the form of the prelude resembles the scheme of a French Overture — a ternary form (we'll call it ABA) in which the opening and closing material (the "A" material) is slow and stately, with dotted rhythms and scale runs, and the middle section (the "B" material) features fugal imitation. In this case, instead of ABA, we have a five-part structure ABABA. This 5-part concept is a gross oversimplification of the form (completely ignoring secondary thematic material), but it serves the purpose at hand.

The piece opens with a clear question / answer phrase structure, using a descending scale motive embedded within chords in half notes which cadence on suspended harmonies. [N.B. The embedded audio clips in this blog post are live recordings of me playing the St. Bavokerk Müller organ sample set (Voxus) using Hauptwerk.]

We'll call this the "A" material. After some sequencing, a similar phrase structure takes place in bar 17, beginning on the dominant (B-Flat), this time moving to the relative minor (C-Minor), also with suspended harmonies.

NOTE: The passage above becomes important for understanding how Bach transitions from the "B" material back into "A".

There is also a subsequent varied statement of this question / answer harmonic pair developed using more active scale runs, helping to warm us up for the B material, which is more active, consisting of shorter note values (16ths) accompanied mostly in quarter notes. The B material is developed in such a way that we become "swept away" as it were, so that we might even almost forget where we came from, and the return of the opening material becomes all the more pleasant.

The Art of the Transition

Anyone who attempts to compose a piece of music in which multiple themes are supposed to appear will find out how challenging it can be to transition from one theme to another. In such a piece, assuming the material is solid, the trickiest parts to write are likely to be the transitions. In the baroque style, transitions are usually done using cadences. In this prelude, there are four significant transitions which take place between the A and B material. The first, moving from A to B, is found at bar 71, a cadence in C-Minor.

The subsequent transition back into the A material is made to sound natural by immediately engaging in a sequence after a suspended harmony on F-Minor in bar 99. Recalling our note above, you may notice that this A material is a transposition of the sequence which started in bar 20.

So this turns out to be a transposition of the opening material in the subdominant, where the transition enters at the equivalent of the relative minor suspended harmony we saw in bar 20 (before: C-Minor in the key of E-Flat, here: F-Minor in the key of A-Flat).

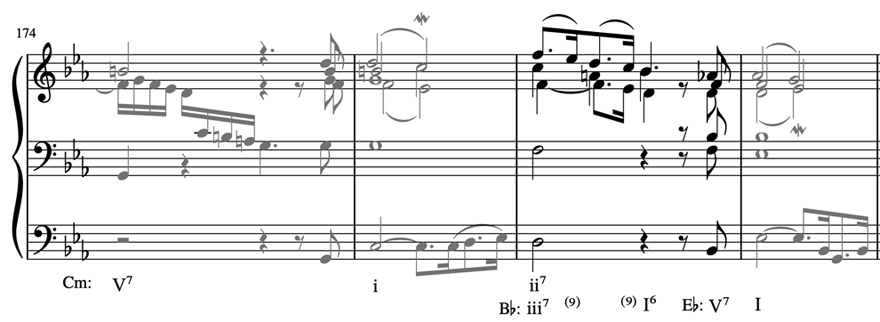

Later, another transition into an extended treatment of B appears with a V I in E-flat (the home key) in bars 129-130.

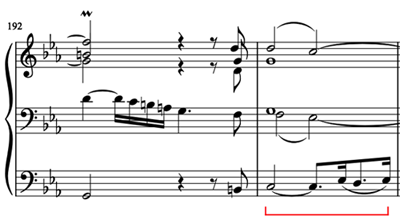

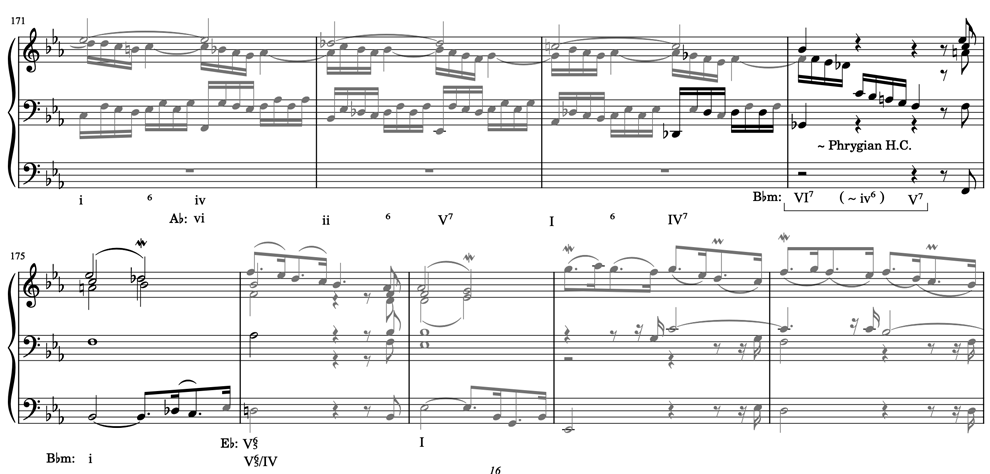

The B material is then developed over a span of 103 measures without return to the A material, until bar 175, where the half notes reappear, not in E-Flat major, but in C-Minor (the relative minor), followed by a complete restatement of the opening (around 30 measures).

Measures 175-176

And here we have arrived at the passage that bothers me, which has in fact bothered me for as long as I can remember. Every time I hear this piece or play it myself, the shift from bar 175 to bar 176 sounds too abrupt — almost like a "cut and paste". It seems like the A material was simply put there without enough care being taken for the transition. Every time I experience this piece (and I keep hoping the feeling will go away, but it never does), I feel like something has gone a bit wrong and something is missing at this moment. Why? Is this just some personal quirk of mine? I don't think so, because there are logical reasons why it sounds not quite right. I will even go out on a limb here and wager that in the 300 years since it's publication, at least one other person has been bothered by this transition.

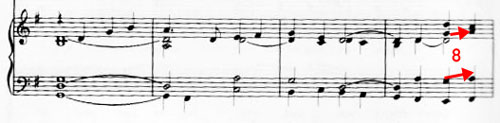

If we compare this passage from bar 174 to the end of the piece with the previous transition from B to A in bar 99 and following, we notice that this second transition would be symmetrical with the first if Bach made the "splice" from bar 174 to bar 193 instead of bar 175, because in both bars (175 and 193) we have essentially the same suspended C-Minor cadence half notes. Did you ever notice that before?

If this transition were to move from bar 174 to bar 193, the closing A section would be exactly symmetrical with the transition in bars 99 and following, and the final section would be 18 bars shorter.

Could this shorter recapitulation have been what Bach started with, and then he decided it was better to restate the whole opening? Not likely. A lesser composer might have done that, but not Bach. Bach knew that the transition would have been much more natural if it had moved from 174 to 193, because that's what he did at bar 99, but if he did that again here, the formal balance wouldn't be right. By including 18 additional bars from the opening, the form is correctly balanced, but the transition is slightly awkward. Bach knew that front-to-back formal symmetry was more important than the transition. In fact, the "surprising" aspect of the transition could in this light be viewed as a deliberate signal to make the formal return of the opening material all the more clear.

While that sounds reasonable enough, the transition still bothers me. Here's why. Before the return of the A material in bar 175, C-Minor has already been established 6 measures earlier (with the B material), so the note B-natural as the leading tone has already been in clear force prior to the transition.

When we reach bar 175, we get a very strong suspended harmony, V over i resolving to i in C-Minor, and the crucial note B-natural sounds in the V resolving to C. In the following measure, the harmony shifts to B-flat Major in first inversion, with almost all voices moving in similar motion. If those two facts seem like clues that something is less than ideal here, you're starting to see why this bothers me.

A Questionable Harmonic Shift

B-Flat Major is in fact a functional diatonic harmony in C-Minor, but it's also the most distant relation, the flat VII. B-Flat Major sounding after a very clear C-Minor in which half of the bar has sounded the leading tone B-natural in the dominant V and resolved it, simply isn't going be the most natural-sounding transition (even when the preceding referenced the key of A-Flat, with the note B-Flat appearing in bars 171-173). The harmonic shift from C-Minor to B-Flat is by nature going to sound a little less than natural, if not slightly awkward, because of the chromatic shift from B-Natural to B-Flat.

Questionable Voice-leading

Too much similar motion is not good for counterpoint, and exactly that weakens this crucial moment. The D in the bass is supposed to be a leading tone in E-flat Major, but that isn't what it sounds like when it arrives. Instead, we are distracted by the chromatic shift from B-natural to B-flat (downward!) which works against the D sounding like a leading tone needing to resolve up by step. The soprano, alto, and tenor all move up. The bass technically steps down, but its line in bar 175 is a neighbour group around D, so the impression is still vaguely of stepping up from the downbeats of these two measures: C to D.

Alternative 1: A First Attempt

Could this transition be improved? Is there something "missing" here? To try to answer these questions, I wrote some alternative transitions. The first attempt was simple, using the advice "don't worry about anything, just follow your ear" (which is good for getting a quick result — not necessarily the best result, but a quick one). So I began with the piece up to bar 175 as written, and imagined that the score broke off there, with some music missing, then picked up again in bar 176. What might be missing? Again, the goal of this first attempt was not to write the greatest not-actually-missing bars in history. It was to have something that did the job, which could then help give clues about how to perhaps do it better. Following my ear wherever it led, I ended up with the following five measures:

I understand that at this point you might feel like telling me how awful this is, but let's look at what happens here objectively if we can, and see how it relates to the original. Instead of directly cancelling the B-natural leading tone with a B-Flat, A-Flat gets raised to A-natural so that the B-Flat sounds more natural along with a raised F-Sharp, to lead to G-Minor. This bass line is reasonable voice-leading, since it is in contrary motion with the soprano (and is the same bass pattern Bach used at the opening of the work — a downward tritone). The same harmonic progression then happens in D-Minor (a sequence), but with a thinner texture and a deceptive resolution of the dominant. Then comes a quick step backward on the circle of fifths, and a statement of the B theme appears in B-Flat (with a "hand-off" between the soprano and tenor), with another unexpected backward fifth modulation so that B-Flat clearly becomes the dominant of E-Flat.

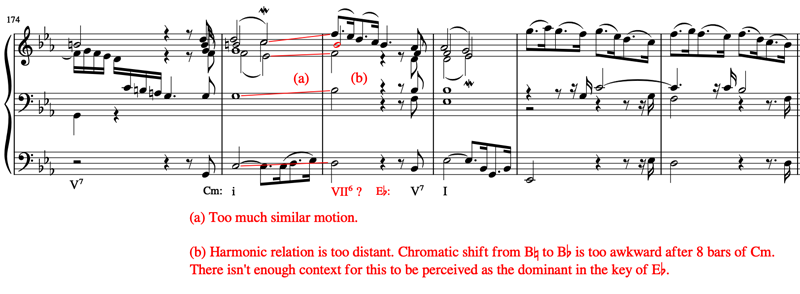

This works, but feels a bit long, and has a harmonic direction that may not be entirely convincing. The cadence in G-Minor seems suspect. The problem is that that the symmetry of two suspended half-note harmonies of the opening theme is broken, since we now we have three such suspended harmonies (C-Minor, G-Minor, E-Flat). This raises a point in favour of Bach's version: simple symmetry. There are other issues within these five bars. Below, I've marked my score as if I were one of my students.

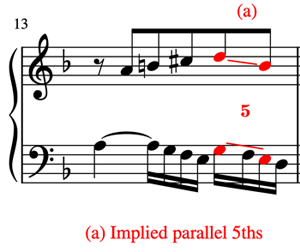

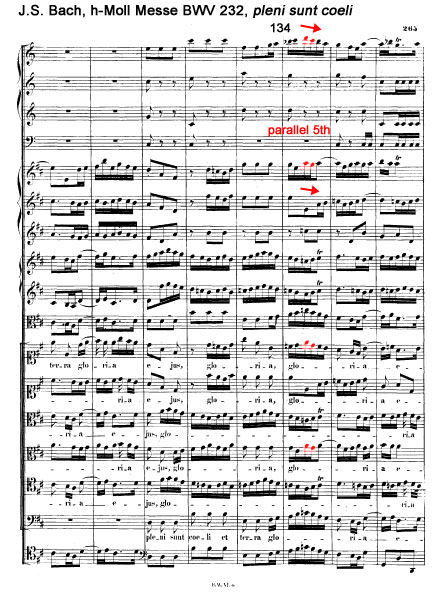

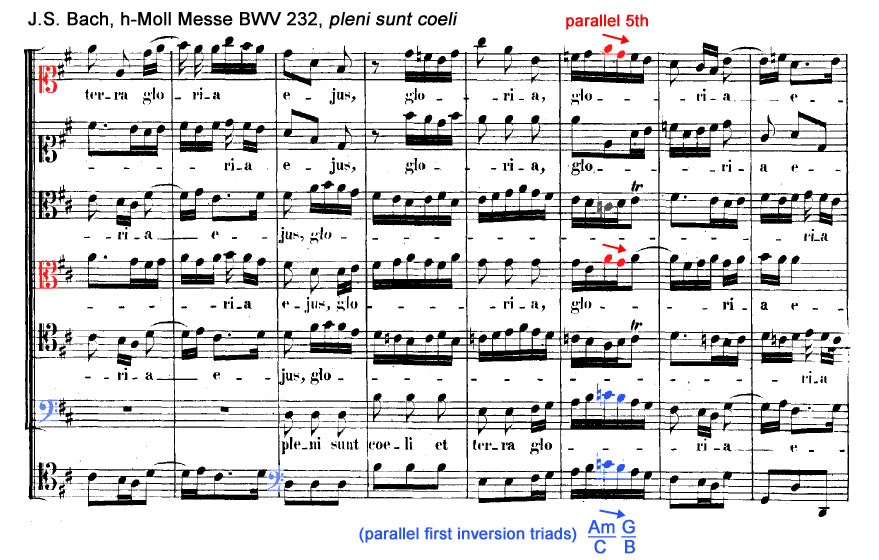

If anyone out there is concerned about the implied parallel 5ths between the tenor and bass in bar 180 above, take a look at my previous blog post which shows how Bach wrote implied parallel 5ths and implied parallel octaves, as well as one actual parallel octave / unison in this piece.

Alternative 2: A Second Attempt

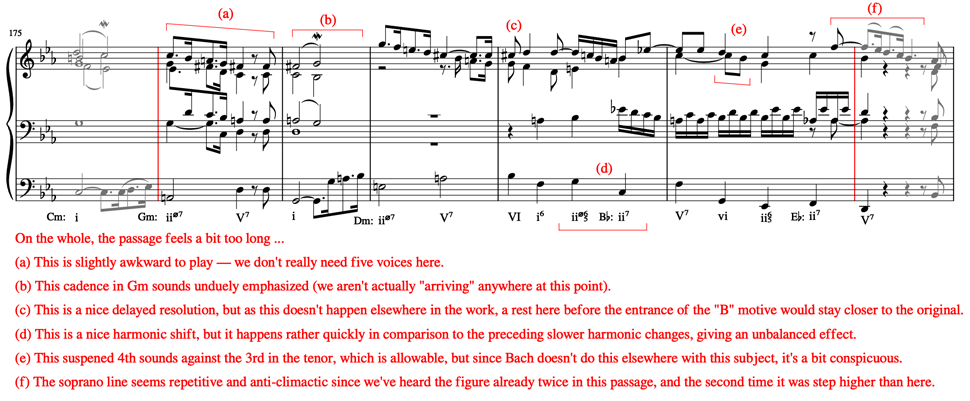

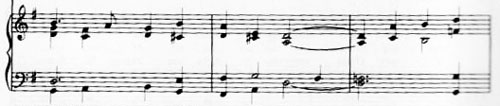

Considering all of the issues in my first try, I made a plan for a second attempt, aiming for something as short as possible, trying to keep whatever might have been good in the first attempt. The result was the following two measures.

Here, the bass line from bar 175 to 176 remains as Bach wrote it, and the soprano line in bar 176 is almost the same except that what was a B-Flat is here a B-natural, and the harmony is D-Half-Diminished, so we stay in C-Minor. A deceptive resolution of V then moves to A-Flat, followed by a ii V I in E-Flat. Harmonically, this is more logical than the first attempt, and it seems to do the job without raising any obvious red flags. The symmetry of the original is still sort-of there, delayed by one measure.

This version sounds less invasive than my first attempt, but the fifths by contrary motion in outer parts bothers my ear, and I'm also left with the feeling that there isn't enough space, because we plow through with all parts sounding instead of dropping out voices as in the original. So another important aspect of the original becomes clear: space!

Another apparent weakness of this version is that we've just cadenced with a 2-5-1 in C-Minor, so the 2-5 (D-Half-Diminished to G) in the new bar 176 ends up sounding slightly repetitive.

Alternative 3: A Revised First Attempt

Returning to the first attempt to try to improve it, I noticed that the cadence in G-Minor could be removed, the deceptive cadence could be sequenced instead, and the soprano line transitioning into the suspended harmony in E-Flat could be altered in a way that would both make the melodic direction of the phrase more logical, and also produce a broader symmetry within the composition, so I made those revisions, as shown below.

With the cadence in G-Minor removed, the harmonic rhythm is certainly more consistent. The transitioning soprano line in the last bar now begins on A-Flat, higher than its previous entrance, and is now modelled after the alto in bar 174, creating a new symmetry. On the whole this should give a more natural and convincing impression, but it remains quite far away from the original.

At this point another important aspect of the original became clear to me, namely that the entrance of the pedal (which has been absent for about 15 measures prior to bar 174) is associated with the return to the A material. Here we don't get that same signal. Foiled again?

Alternative 4: A Revised Third Attempt

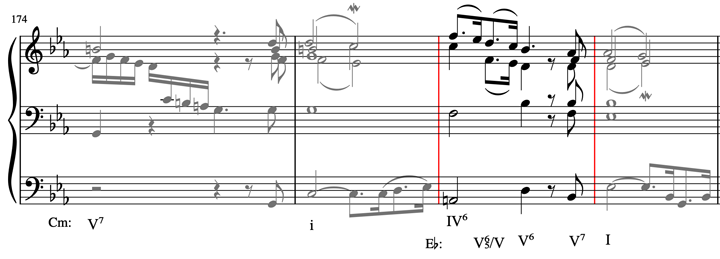

Since I saw that none of my alternative ideas matched the straightforward simplicity of the original, I changed my focus to the four measures 174-177 which serve as an analog to the opening four bars of the work. Those opening four bars are shown below, followed by bars 174-177.

It occurred to me that without adding any new measures, a simple change in harmony could bridge the keys of C-Minor and E-Flat Major in a more functional way, while also improving the voice-leading. The trick would be, instead of moving directly to B-Flat, the bass would move to A as the 3rd of F Major, which would then move to B-Flat in first inversion on beat 3. By holding only the B-Flat in the soprano as a dotted quarter and making all the other parts on beat 3 quarter notes followed by eighth rests on beat 4, the feeling of rest before the suspended harmony on E-Flat could still remain half-preserved. Here is the result of this thinking:

F Major is functional in both keys, serving as a more reasonable pivot than B-Flat. This option somehow manages to sound less convincing than the other attempts. One reason for this may be that Bach tended not to write two first-inversion 5th-related triads in a row where the bass sounds like it should be in root position but it isn't. Another reason mentioned earlier would be the fact that all voices remain present. It also contains implied octaves by contrary motion. Otherwise it's possible that the this version may be too similar to the original (which for those of us who know this piece is burned into our brains), so that cognitive dissonance is too strong, and it just "sounds wrong". Which begs the question, for someone who didn't know this piece to begin with, how would this version fair against the original?

Alternative 5: A Completely Different Approach

After all this bother over measures 175-176, where C-Minor is the given which causes so much trouble moving to B-Flat, it dawned on me that the sequence prior to these measures could simply be redirected so that we don't move to C-Minor in the first place. Instead, the sequence can move to B-Flat Minor, using a Phrygian half cadence. The trick is to use D-Flat, G-Flat and B-Flat instead D, G and B, since the sequence itself can naturally move in either direction. Once we have an implied F dominant instead of a G dominant, we can cadence in B-Flat Minor instead of C-Minor. Then the B-Flat dominant chord functions more strongly in both keys, as an altered tonic (secondary V7 of iv) in B-Flat Minor, and as V7 in E-Flat. An added 7th in the tenor on the dominant strengthens the shared harmonic function. Spoiler alert: this is going to sound a bit clumsy!

The clumsiness comes from two things: first and foremost, the single voice trailing off (as the original does) doesn't have quite enough context to state a totally convincing Phrygian half cadence. Secondly, the soprano stepping down from C to B-Flat instead of B is slightly conspicuous. The good news is that these things can be improved. Adjusting things slightly to move to B-Flat sooner, leaving in the other parts at the cadence, gives a better result. There would be any number of ways to work out the voice-leading for this; below is one possibility.

Although the harmony is clear and functional, the feeling I get from this version is a bit painful. B-Flat Minor is a lovely but rather torturous key in relation to E-Flat Major, the resolution on the high D-Flat sounds slightly too strident, and the chromatic shift to B-Flat dominant with the 7th in the tenor is too distressful at this moment.

So another trait of the original appears to be superior in comparison. Above, the soprano line steps down from E-Flat to G, but has to do an intervening chromatic shift from D-Flat up to D. Bach's version simply steps down diatonically from C to G — much simpler.

It would be possible to resolve the suspended harmony to B-Flat Major instead of B-Flat Minor to avoid the upward chromatic shift during the descent, but where do we stop? At this point, I think the lessons have been learned.

Conclusion

Are any of these alternatives an "improvement" on the original? No, I wouldn't go that far, although when I play the prelude using any of the more successful attempts, the awkwardness of the original harmonic motion and voice-leading is gone, and for me, that's a better feeling than I get from the original. That might not be the case for you, or for anyone else on the planet, but that isn't the point of the exercise. I've learned quite a few things about why the original is the way that it is, by figuring out some of the things that make it good in comparison to possible alternatives. Obviously, if I hadn't made the effort, I wouldn't have learned these things. That's justification enough for allowing myself to "rewrite" the music of the master. There are those who will protest, claiming that what I've done here is disrespectful. I've received these kinds of comments on social media many times before: "Who are you to ruin this music?!", "Disgraceful!", etc. Let's please not be so uptight. Rewriting Bach's music is a very good way to learn.

Was everything I learned from this exercise already obvious to you? If so, then congratulations for being a few steps ahead of me! If on the other hand you learned something from what I've done here, I'd be glad to hear that. Especially if my experiments inspire you to come up with your own alternative versions of passages that bother you, I hope you'll share those. And lastly, by the way, if you can't think of any passages that bother you, you may not be listening closely enough …

Peace,

Aaron

Parallel octaves and 5ths in BWV 552a (St. Anne, Prelude)

May 09, 2023

BWV 552 is the great St. Anne Prelude and Fugue found at the opening and closing of Bach's Clavierübung III, published 1739.

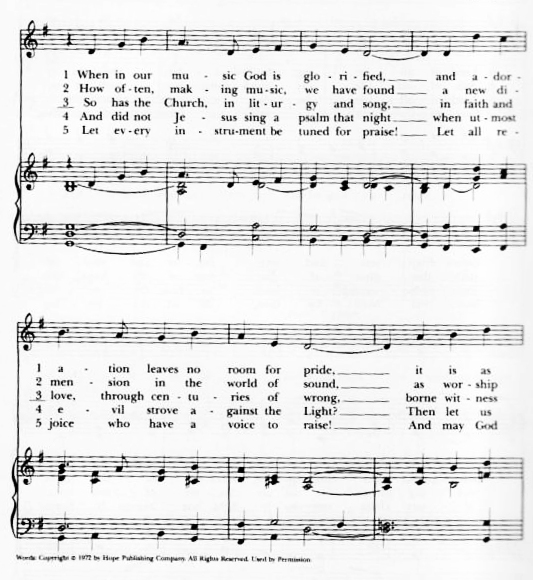

In case you don't already know, the nickname St. Anne wasn't used by Bach. It comes from the similarity of the fugue subject with the tune known in the English-speaking world as St. Anne, written by William Croft (1678-1727), to the text O God, Our Help in Ages Past, by Isaac Watts (1674-1748). Researchers believe it's unlikely Bach knew of the tune. The fugue subject is also related to one Bach had used earlier in his career, in the Prelude in E-Flat Major (same key) in the WTC, Book 1. Today we're looking at the prelude, which Bach marks Präludium pro Organo pleno, a large work — in fact the longest prelude for organ that Bach ever wrote — which has multiple themes.

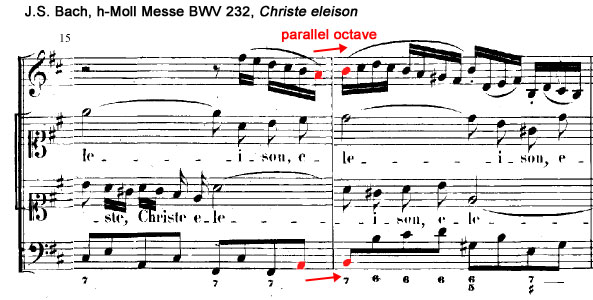

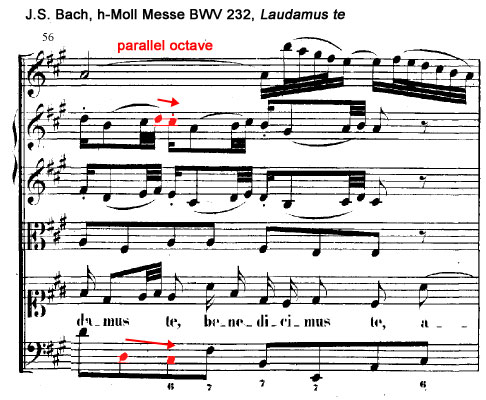

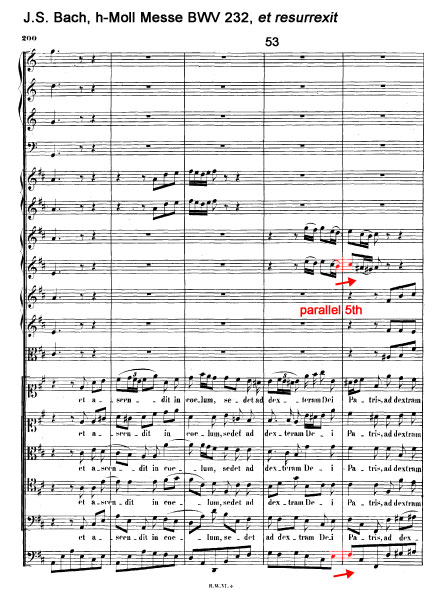

There are some voice-leading anomalies in this piece. The most striking of these is found in bar 67, where Bach writes a real parallel unison (and / or octave, depending on how you want to interpret the pedal part).

The thing about this is, nobody listening is ever going to hear a parallel octave or unison there. Organ registration is in fact based on adding parallel octaves and 5ths. The indication organo pleno means that many octave doublings and mixtures (which include 5ths) are expected to be used in the organ registration. When the pedal part moves here in a parallel unison with the tenor, the relationship between the voices simply can't be heard as such. It's even likely that the pedal will be sounding (in part) exactly the same pipes as the tenor, since the pedal is often coupled to the manual in organo pleno which again has been deliberately specified in the title of the work.

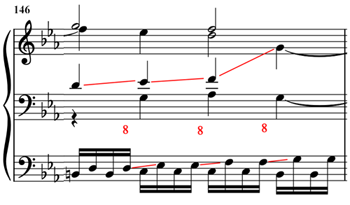

But it doesn't stop there. Bach also wrote implied parallel octaves in this piece, in measures 137, 146, and 150.

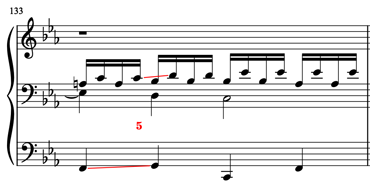

And if that's not enough rule-bending for you, in bars 133, 142 and 158, Bach also writes implied parallel 5ths with this same material.

So students take note: Bach gets away with writing real parallel octaves / unisons when it's something nobody will ever hear, and he shows how these kinds of implied parallels can in fact be used, and will not sound wrong. But keep in mind that it takes a master to work magic like this. Chances are we're not quite on the same level as Bach. Like so many other things in this art, there are a great many more ways to do it wrong than there are to do it right. That's why students are simply told: "don't do it".

Next time we'll continue looking at this monumental work, taking a very close look at one particular passage — in fact it will be another episode of "Passages that bother me".

Until then,

AAH

Good-sounding parallel 5ths

April 16, 2023

There are cases where parallel fifths sound good. Sometimes even very good. Are these good-sounding cases still "wrong"? An interesting question!

Today I was practising at the organ, playing through the Prelude and Fugue in G Minor, BWV 535, in which Bach wrote one of these good-sounding parallel 5ths.

What makes this particular case sound so good is the suspended fourth in the soprano. Bach made sure to move the bass in contrary motion with the inner parts. It should also be mentioned that he could have easily "corrected" the passage by raising the E, so that the fifths would be unequal. But he didn't do that, we would have to assume intentionally, because the sound would not be the same.

There are times when I've found parallel fifths in my own music, sometimes already published, and have "corrected" them in a second edition. My opinion on this has changed over time. I think this example shows that parallel fifths are not always "wrong".

Of course, it's my job to point out parallel 5ths to students, regardless of the exceptions. But, it's also part of my job to explain the exceptions. Once a student has advanced beyond making simple mistakes, whether something like this is "wrong" starts to become a more personal matter.

Ultimately, composers have to decide these things for themselves. Count Basie's "If it sounds good, it is good!" comes to mind, which I like, but which also needs a qualifier, because it's only relevant for those who can truly hear and understand everything that's going on. Only then does it become a matter of taste.

Peace,

Aaron

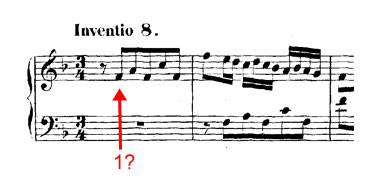

Is this bad invertible counterpoint? (BWV851)

January 19, 2023

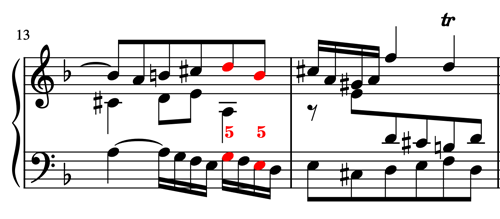

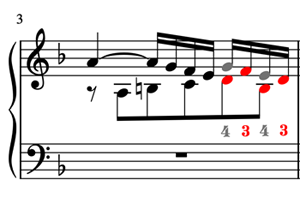

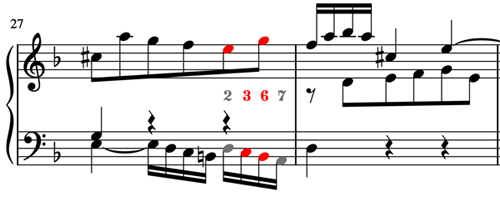

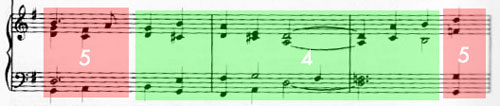

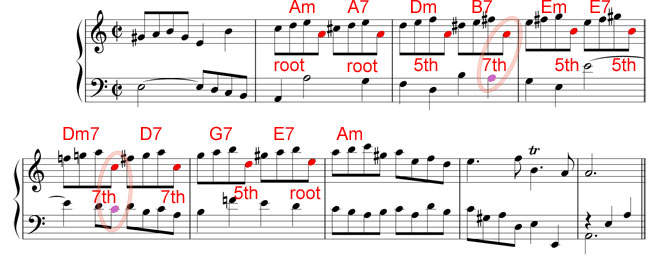

One of my students recently asked an interesting question about invertible counterpoint. He pointed out a passage in Bach's fugue in D Minor from the Well Tempered Clavier, book 1 (BWV851). In measure 3, there are 4ths between the soprano and alto (the only two sounding voices) on beat 4 and the 'and' of beat 4 (the 4ths are marked in red).

The same configuration happens again in bar 6 between the soprano and bass, but it's not necessary to show that, since this configuration was not cause for the question. The question comes from the observation that Bach uses these same patterns in inverted positions in bar 13. In other words, this is an instance of typical double counterpoint at the octave. Do you notice that things look a little suspect here?

Here in bar 13, we see what looks like implied parallel 5ths between the soprano and bass! What's going on? Isn't this bad invertible counterpoint? How did Bach get away with this?

If we take a closer look at bar 3, we notice that both of the 4ths are accented dissonances. The harmonic context makes this clear. The F and the D, both consonant 3rds, are the tones which determine the harmony, not the G and the E (the dissonant 4ths). Here the red notes are showing consonances and the dissonant notes / intervals are marked in grey.

To stress this point, we can imagine an opening where in bar 3 the accented dissonances have simply been removed.

Of course, Bach didn't write that. But that is what's underneath what Bach wrote. When Bach inverted the parts as written in bar 13, it's a similar situation. The offbeat 6ths determine the harmony, not the 5ths.

This is, we must admit, an extremely precarious thing to have done! The middle voice A has been circled, because without that note, the whole structure falls apart! In two parts, this inverted form would simply not fly.

The 5ths are way too conspicuous when we have only two parts. A clear no-go. The structure needs that A in the middle voice, not only to clarify the harmony, but also to draw attention away from the implied 5ths by sounding in close dissonance with the bass (a clashing 2nd). A very clever move by Bach! (If you like clever things, you'll love Bach).

By the way, the markings shown above are what I would normally use when giving feedback to students. Notes, voice leading, patterns, etc. which need attention all get marked, and each point gets a red letter in parentheses, which then is given a thorough explanation (usually the alphabet supplies enough letters for the feedback, but I have in fact had cases where double letters were necessary).

You may be wondering though, how do we explain exactly what is going on harmonically here? Well, it may seem slightly odd, but it's actually pretty typical of Bach. We can add a couple of notes to arrive at a more conventional version which clarifies the harmony.

[N.B. The chord symbol Dm should be Dm/F] Bach didn't write that G-sharp, so the real harmony there is a "suspended" sound, but functionally that middle voice begs to sound a G-Sharp at that point, giving a second inversion diminished triad. If the voice were to continue sounding, then it would return to A on the downbeat as shown, resulting in a second inversion A Major triad. Do these clearer harmonies raise any red flags? Yes. Second-inversion flags. This is a pretty logical explanation as to why Bach didn't write these notes. Although the 64 on the diminished chord is passable, the downbeat 64 is very undesirable. We could say it's still there in Bach's actual writing, but the A isn't there, and a 6th without a 4th suggests an alternate root on the 3rd: C-Sharp to E. This is a trick of the trade you can also use to get around some cases of second inversion harmony. Use a rest, omit the 4th, and the sounding 6th is often acceptable, as it is here.

Bach was very careful in this piece not to repeat this configuration of voices. Bar 13 is in fact the only place in all of 44 bars this situation appears. The voices appear only one time again in a similar structure, in measure 27, in only two parts, but there Bach uses the inversion of the subject so that the structural tones and added dissonances form an entirely new constellation.

Much more time could be devoted to this. It would be easy to spend hours getting into the details of this piece. And it would be time well spent, very rewarding study. That's how Bach's music is. In the whole WTC, from one piece to the next he does such daring things, and if you look you'll find instances that just shouldn't work, but they do. Including parallel fifths! They are there in the WTC. I won't tell you where. See if you can find them!

Until next time,

AAH

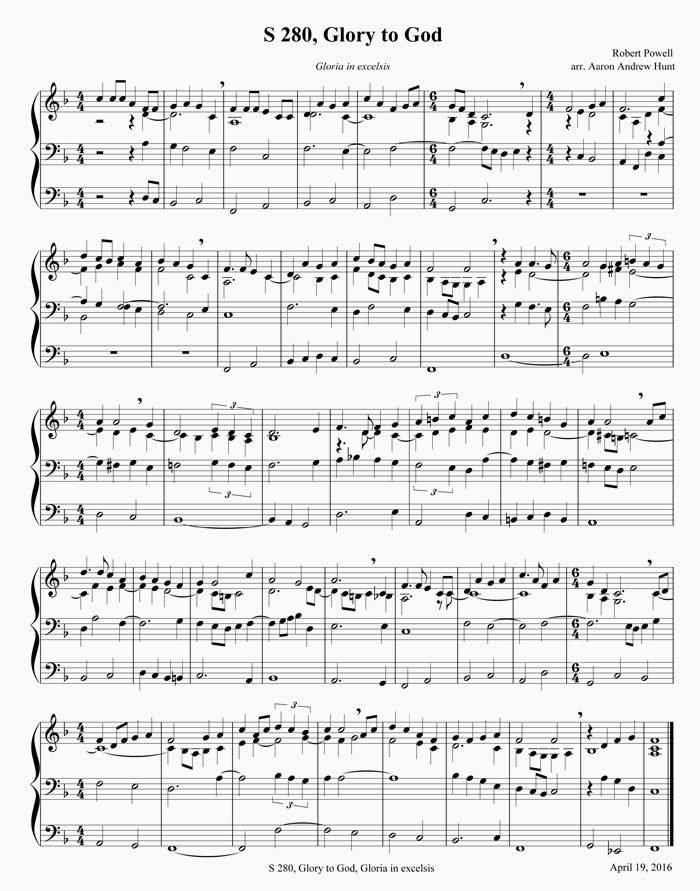

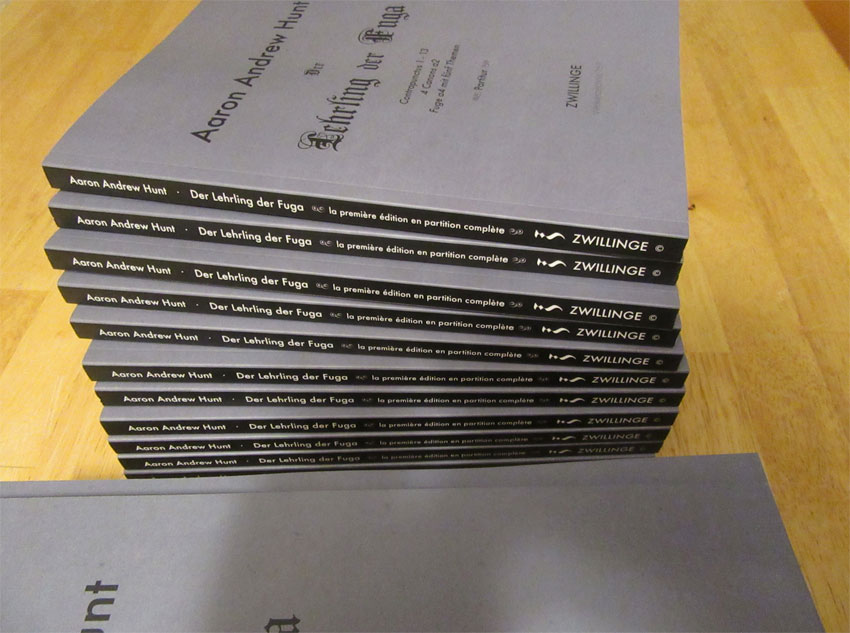

New scores!

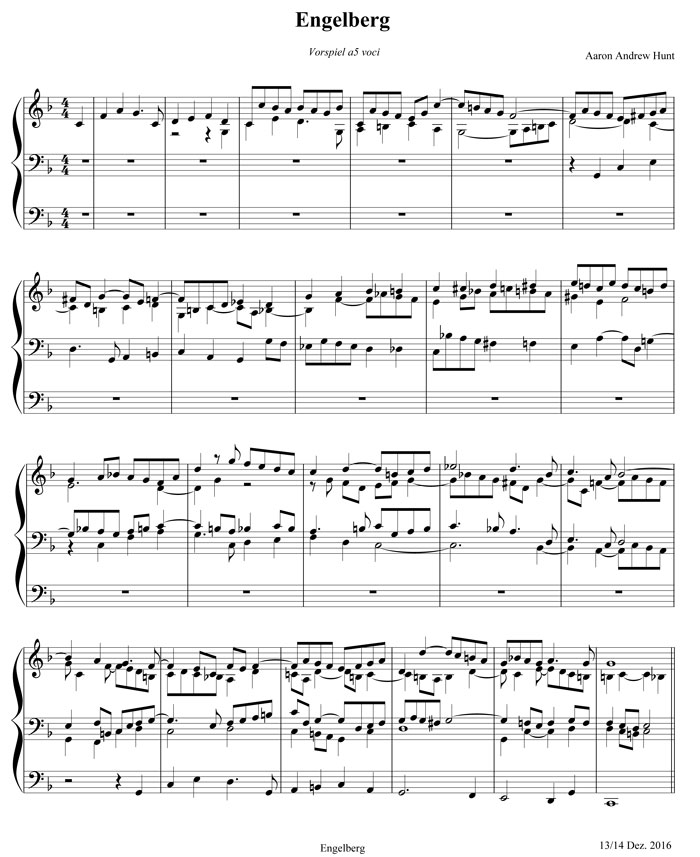

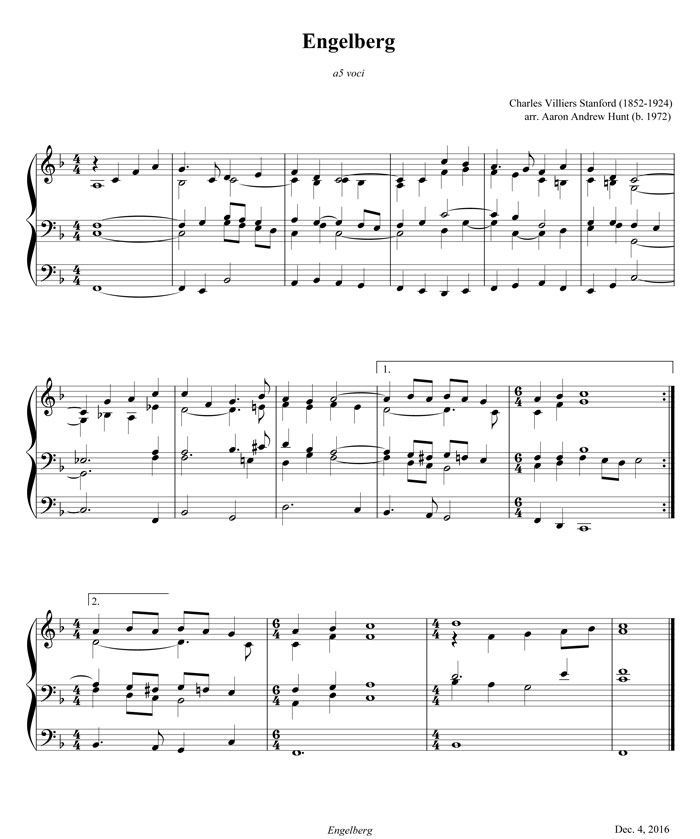

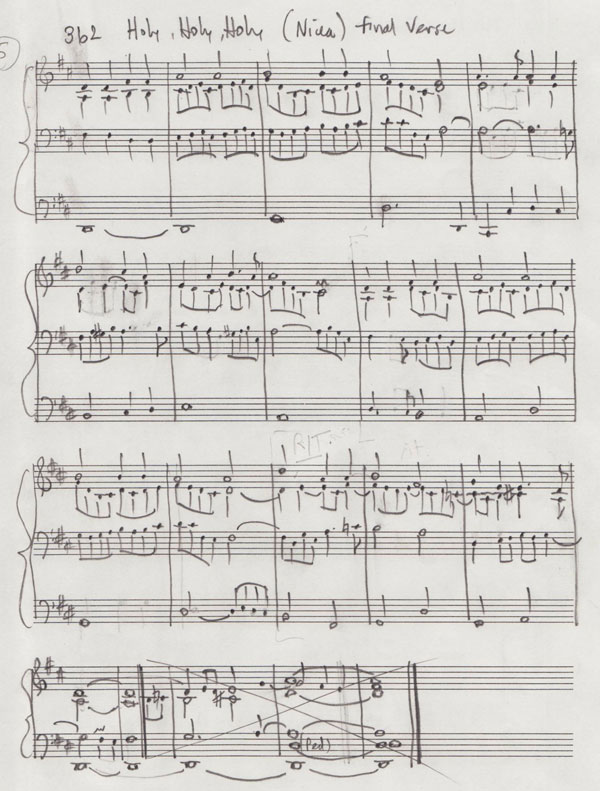

January 05, 2023

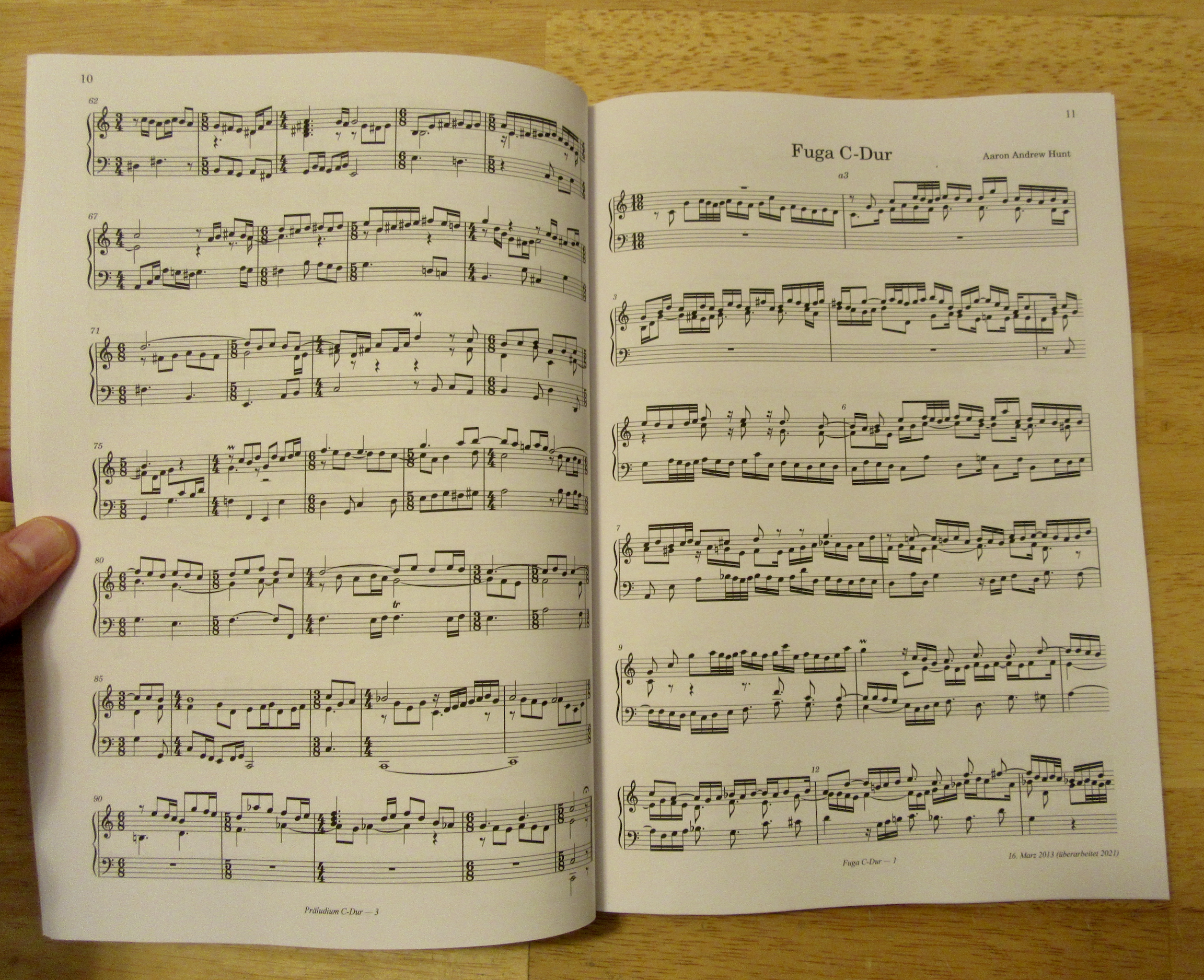

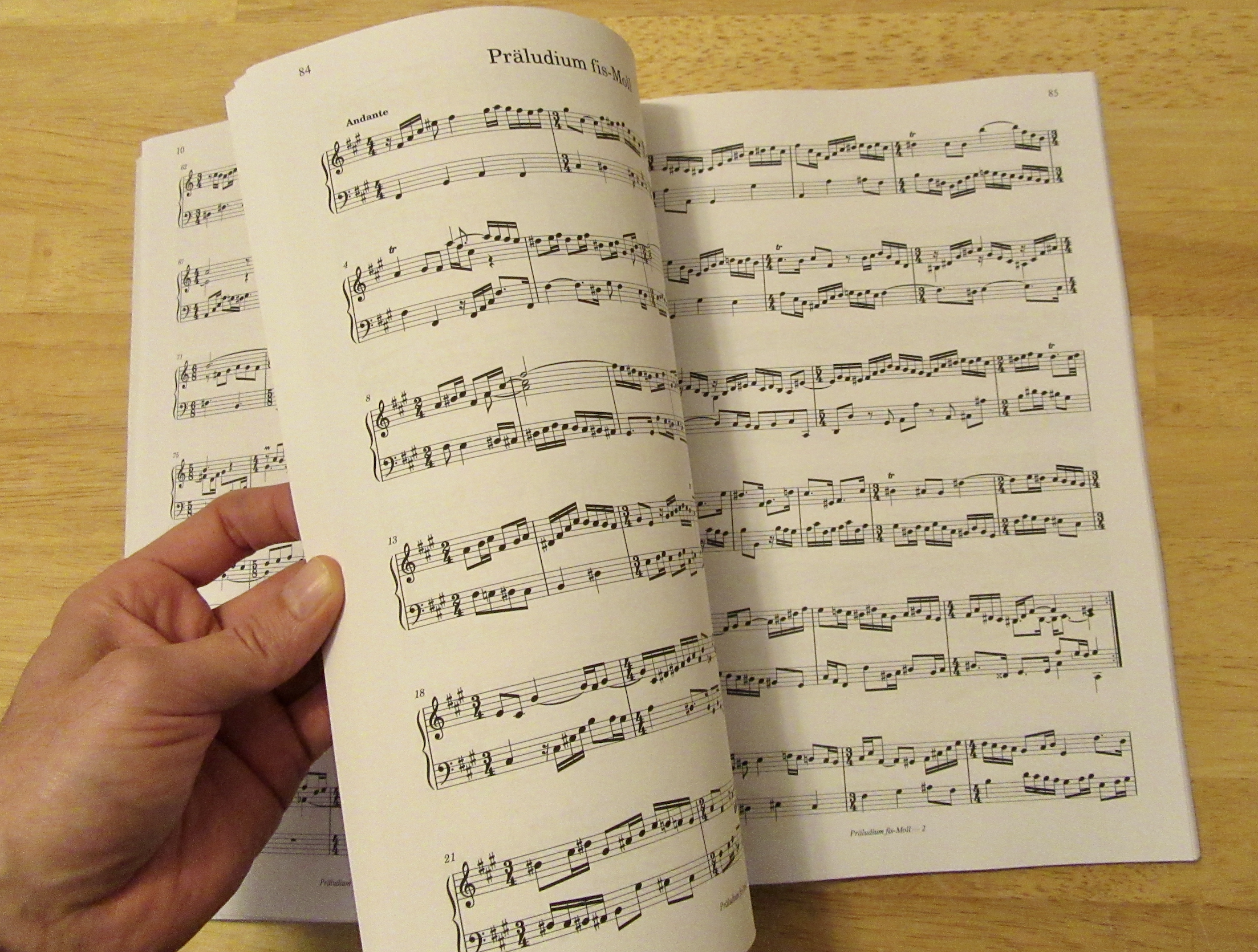

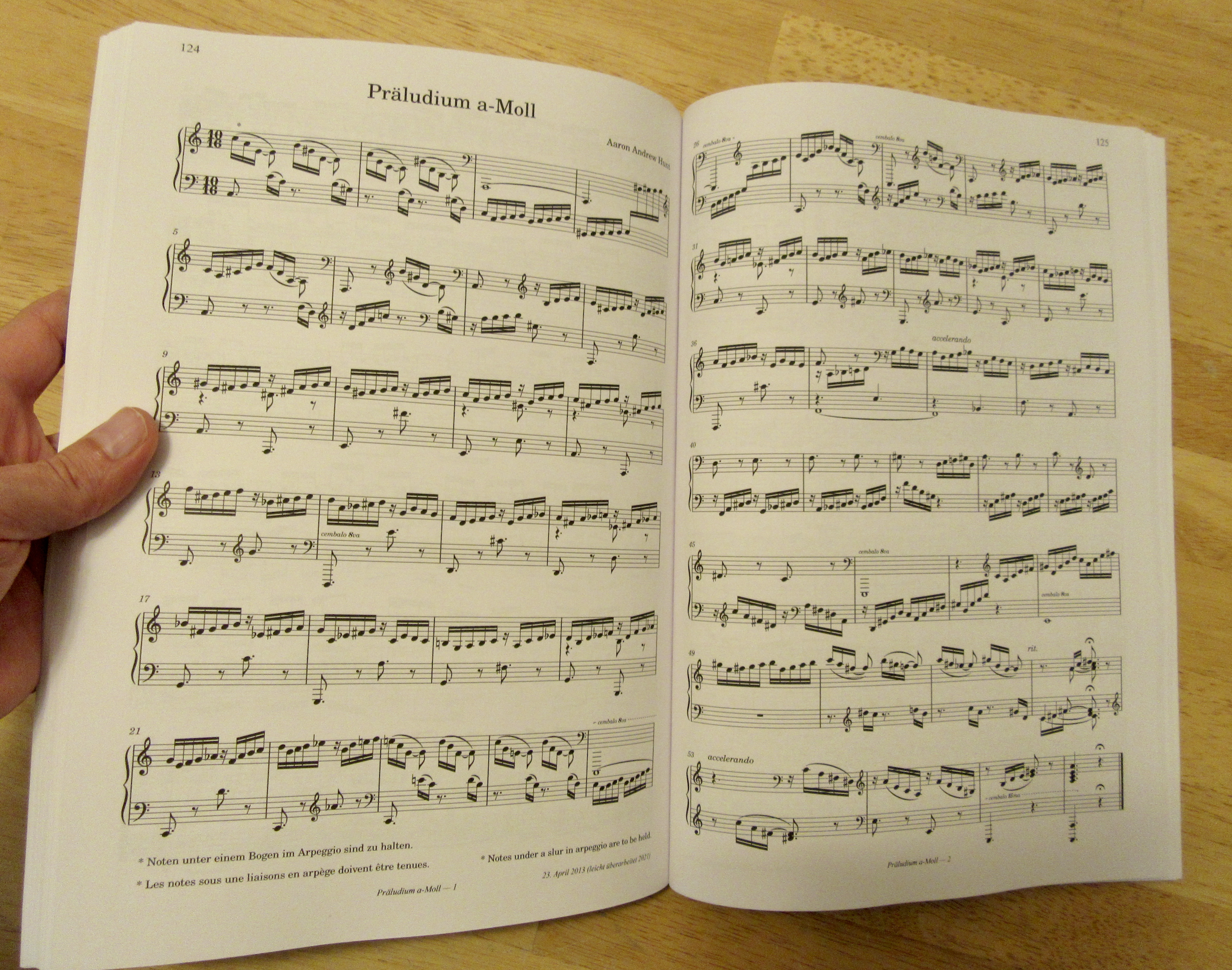

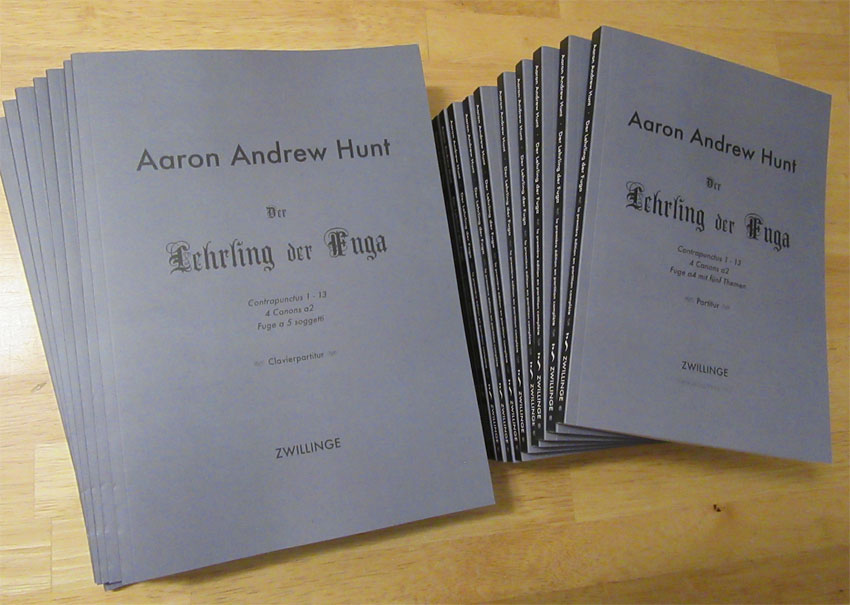

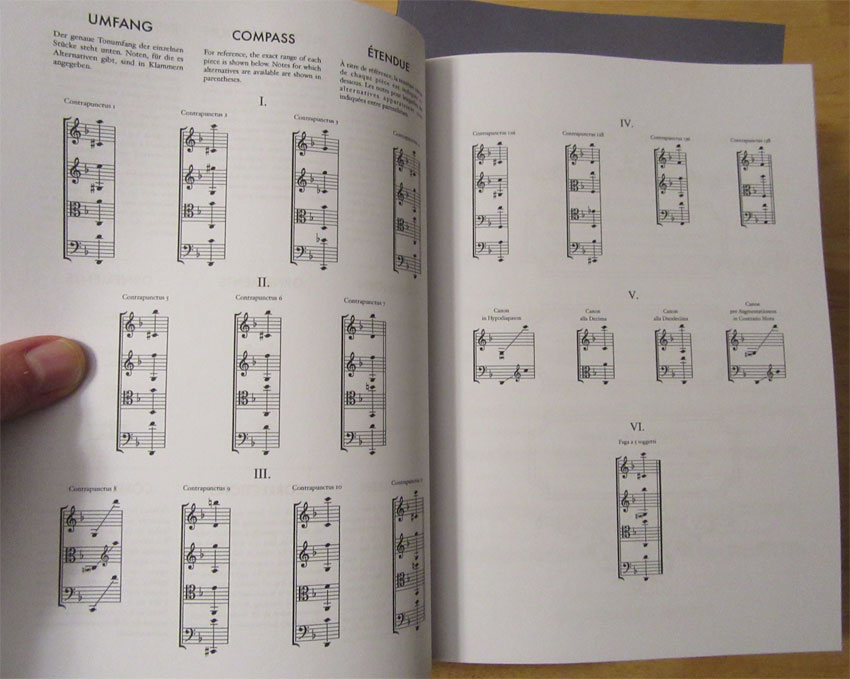

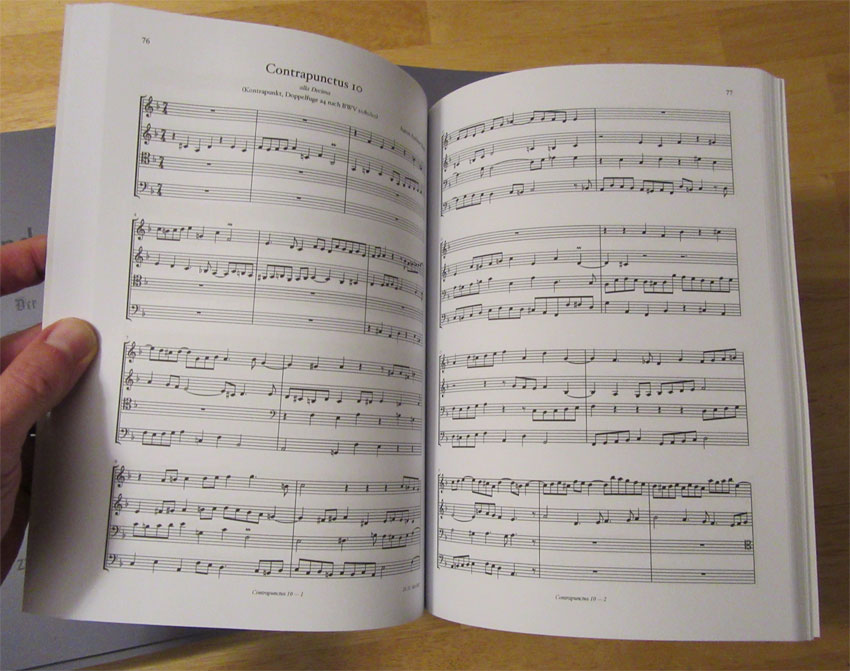

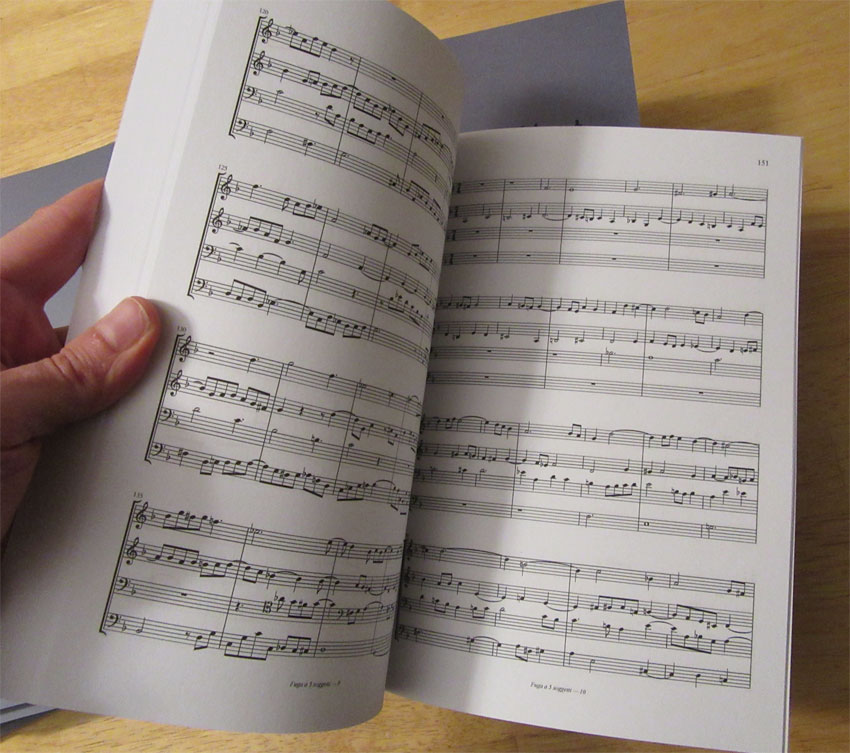

The first printing of »Der Lehrling der Fuga« (The Apprentice of Fugue) arrived today! I'm pleased with these results. The margins and the size of the notes and so on — things which are much harder to get right than you might think — all look right on, for both scores. The keyboard score is a normal A4 book, which is the a good size for reading and performance. The open score, having a higher page count, isn't really intended for performance, and I find it's especially attractive in the nearly Taschenpartitur format of 17x24cm (larger than most pocket scores). Having two different sizes brings an added benefit, that the keyboard score and open score won't accidentally get mixed up when shipping. Take a look!

To the brave few who have already placed an order, thanks for your trust and patience. The books will be in the mail in the morning! If you'd like to have one of these, please place an order at Zwilling Verlag.

Happy new year everyone,

Aaron

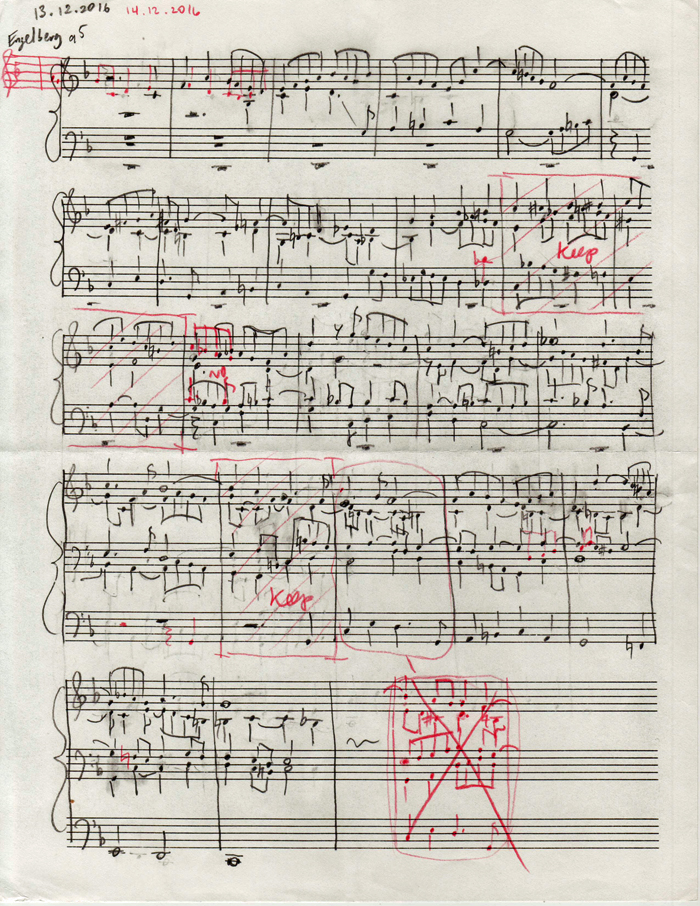

Der Lehrling der Fuga (The Apprentice of Fugue)

December 14, 2022

As promised, the two-hour recording of Der Lehrling der Fuga (The Apprentice of Fugue) has been published today on Bandcamp.

If you've ever wondered what odd meters like 7/8, 5/8, 11/8, and 15/16 could possibly have to do with Bach’s Die Kunst der Fuga (The Art of Fugue), here's your chance to find out. Please note: this music is not an adaptation of the original. The music is newly composed, using the subject from the original, strictly following the techniques and formal models used by Bach.

The score is available in both keyboard reduction and open score, at Zwillinge Verlag.

Peace and blessings,

AAH

Der Lehrling der Fuga

December 02, 2022

I’m pleased to announce my latest work, Der Lehrling der Fuga (The Apprentice of Fugue), written during the past year — a time which has been devoted to intense study of Bach’s Die Kunst der Fuga (The Art of Fugue). This work is the result of a life-long fascination with Bach’s masterwork.

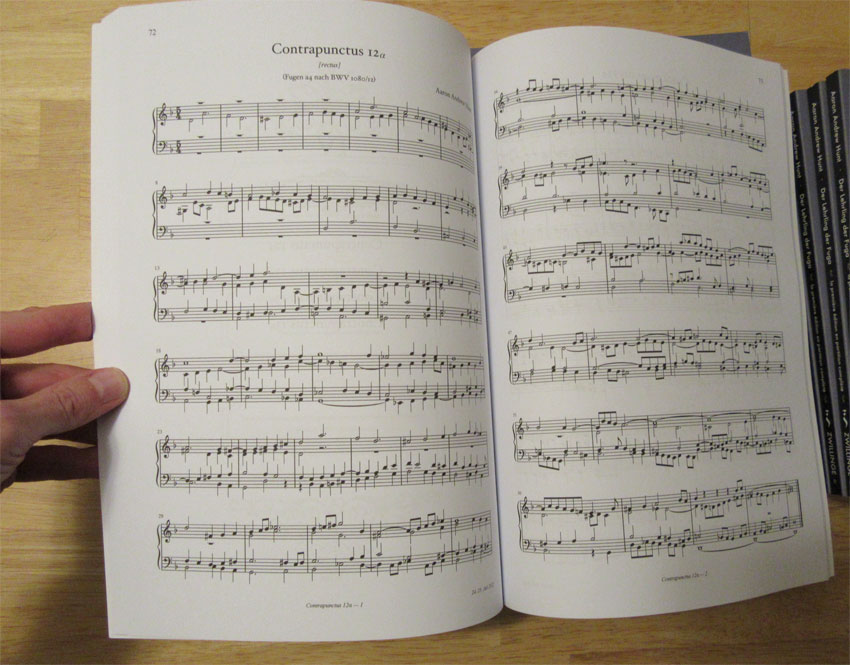

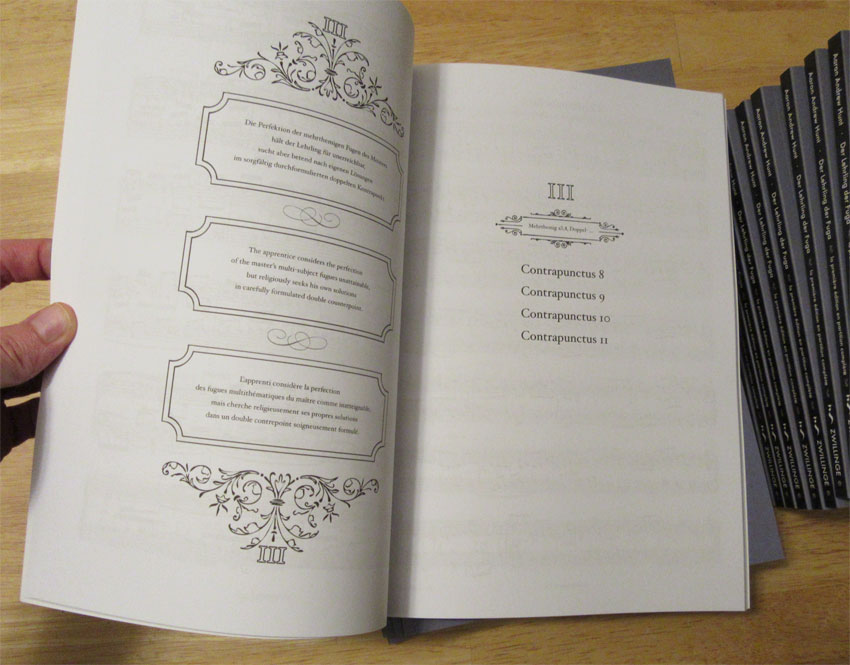

The structure of the original is followed, with 20 pieces arranged in six Parts: Contrapunctus 1-4, 5-7, 8-11, 12a-13b, four canons, and a final fugue. Each section is introduced with a short text.

Although we know now that Bach’s "unfinished fugue" does not belong to the Art of Fugue, since it has been included in all publications of BWV1080, and for other obvious reasons, my work also closes with a multi-subject fugue: Fuga a 5 soggetti (with not three, but five subjects).

A pre-release recording (PART I only) has been posted at Bandcamp. The rest will be released December 14. The score will be released later this month at Zwillinge Verlag, available both in keyboard reduction, and in open score (pre-orders may be placed now).

Thanks for your support,

AAH

Why are these parallel 9ths okay?

November 19, 2022

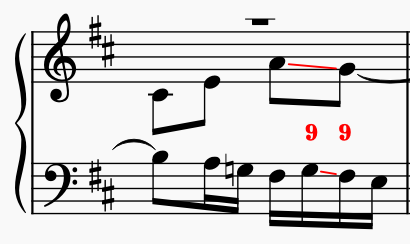

In my teaching, I try to avoid fixing student work by writing out a corrected version. Instead, I try to clearly mark every element that's problematic and do my best to explain why each thing has been marked, and what could be done to correct each problem. This way students are led to their own solutions. Sometimes though, to save time, particularly if we've been working on something for quite a while and problems are still cropping up, I might go ahead and just show something by writing out a new version for the student to compare with their version. Last week I did that for one of my students who is working on his first fugue expositions, and it so happened that what I wrote included the following measure:

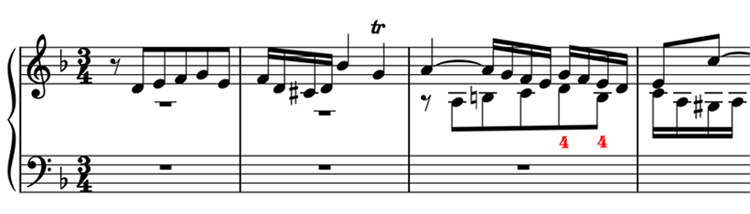

The student then pointed out that this measure contains parallel 9ths. Did you notice them?

He recalled that some time ago I had pointed out parallel 9ths in something he'd written as being a problem. Apparently, these parallel 9ths are okay, but why? A valid question. I explained it this way … The underlying voice leading is parallel 10ths. We can start there and work our way toward the version with the parallel 9ths:

The F-sharp in the bass can be held as a suspension. The dissonant 9th sounds nice, and the F-sharp then sounds like it must move to the E to resolve the dissonance.

To further accent this dissonance while making the lower part more active, the suspension can be elaborated with an upper neighbour. This is where our parallel 9ths come in.

Parallel dissonances of this kind are a fairly common occurrence in Bach's music. Parallel 7ths and 2nds aren't entirely rare, since they result from this technique of emphasising dissonance and keeping voices rhythmically active — which is in fact one of the defining characteristics of Bach's music. Like everything else in this art form, there are a lot more ways to do it wrong than there are ways to do it right!

Best Regards,

AAH

Is counterpoint like chess?

October 24, 2022

Last week, one of my counterpoint students, who is currently working on the basics in two parts, asked me the following question:

Q: "What's it like to get better at writing counterpoint? Do you eventually get faster at considering many possibilities and discard weaker options (e.g. noodling lines), or do you get better at considering a few stronger options? Is it similar to chess or go where a weaker player considers many candidate moves and discards many options but apparently stronger players only consider fewer moves?"

Here's what I wrote back to him:

A: That’s an interesting question. Composing from scratch is enormously complicated, and I think music in general shouldn't be compared too closely with playing a game, but if we take the situation of writing counterpoint against an existing line, then there are some similarities to strategic thinking in chess or go. As with those games, you’ll learn to reject a lot of the “moves" that may seem reasonable to you now, and will get faster at seeing the “good moves" available to you. Eventually you will immediately see the “best moves", as the "expert player” does. Obviously, one can’t expect to achieve that level very quickly. It takes many years. Your confidence level and accuracy of self-perception will improve with time. In these games, the inexperienced players tend to think they know more than they actually do. They have false confidence out of ignorance (until they get demolished by the better player). The best players have worked hard to develop strong skills and the confidence that comes with that, and they will also tend to be humble about that and will want to help the weaker players to get better, because they have learned how difficult the game actually is. — AAH

Organ Recital in Hong Kong — October 15, 2022

October 06, 2022

I'm pleased to share the good news that organist Jonathan Yip (pictured, left) has chosen to perform my Chorale Partita »O Mensch, bewein dein Sünde groß« in recital at St. John's Episcopal Cathedral in Hong Kong on October 15, 2022. Jonathan's recital will conclude the Cathedral's Michaelmas Fair, a series of organ recitals which began in August. This performance will be a world premiere, and quite a unique event considering the length of the partita, which sets all 23 verses of the monumental Chorale text penned by Sebald Hayden in 1530.

The partita was published in 2019 in my book »Sechs Choralpartiten«. After the printed score became available, I decided to share a free PDF score on IMSLP, along with a free recording on Bandcamp (links at Zwillinge Verlag). Video animations of several movements from this and other partitas from the book have also been published on YouTube by Stephen Malinowski (example below).

As is the case with many Episcopal parishes worldwide, the music at St. John's Cathedral is of the highest caliber, which you can hear and see for yourself through the Cathedral's YouTube channel, where weekly choral Eucharist services, Evensong, and other special services are regularly broadcast (most are in English, some are in Chinese). The concert will begin Saturday, October 15, 2022 at 3 PM HKT (UTC/GMT+8).

Best Regards,

Aaron

‘Meet the Artist’ interview

August 12, 2022

A few days ago this short interview was published as part of pianist Frances Wilson's »Meet the Artist« project. I've discovered many interesting performers, conductors, and composers through this website. Take a moment and look around, you may be surprised by the insights shared there.

Best Wishes,

Aaron

Composing the ETK

February 02, 2022

The Equal-Tempered Keyboard has been available since January 2022, and has received a (surprisingly?) warm reception. Some readers have also expressed interest in the "forthcoming" text that is mentioned in the preface. In correspondence with those interested, I've had to admit that that text, tentatively titled "Composing in Equal Divisions of an Octave, 5ET to 20ET", remains unfinished. The idea is to discuss each tuning at some length, showing my approach to working with each tuning, along with musical examples from sketches and final scores. This kind of text can be useful not only for those interested in microtones, but for anyone interested in tonal composition, because each tuning imposes curious limitations on the kinds of patterns that will sound acceptable. For example, have you ever tried writing a piece that sounds minor, but contains no minor thirds? Have you ever written music that contains no perfect fifths? These are the kinds of challenges that arise when working with non-standard divisions of an octave. All quite interesting, but also very time consuming work. Having focused my efforts on completing the music and publishing the book, I unfortunately completely lost my motivation to work on this explanatory text. But I'm happy to report that, after admitting this, I received some encouragement, in the form of donations towards this work. So I will be working on this with an aim to publish as soon as I can.

So far I've determined that the text I've written up to this point (which was done sporadically over many years) is mostly worth keeping, but I will have to redo all of the musical examples, which is unfortunate, but at least better than having to rewrite the entire work. The book is planned as an A5 paperback, probably around 70 pages, but since I consider it worthwhile to translate texts into German and French, the end result will likely be around 200 pages. If the number of pages increases substantially, I suppose translations may also be printed separately, we'll see.

Thanks to those who are donating for this work. If you would also like to help, please support this project.

Stay well,

Aaron

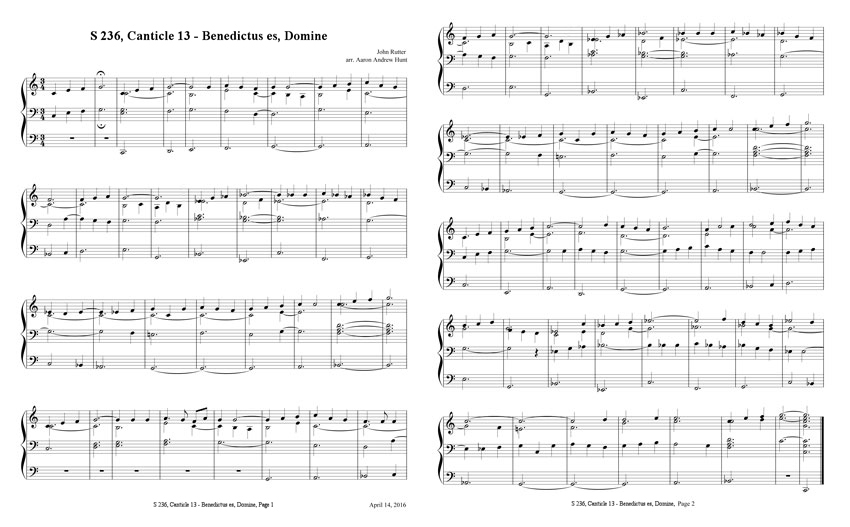

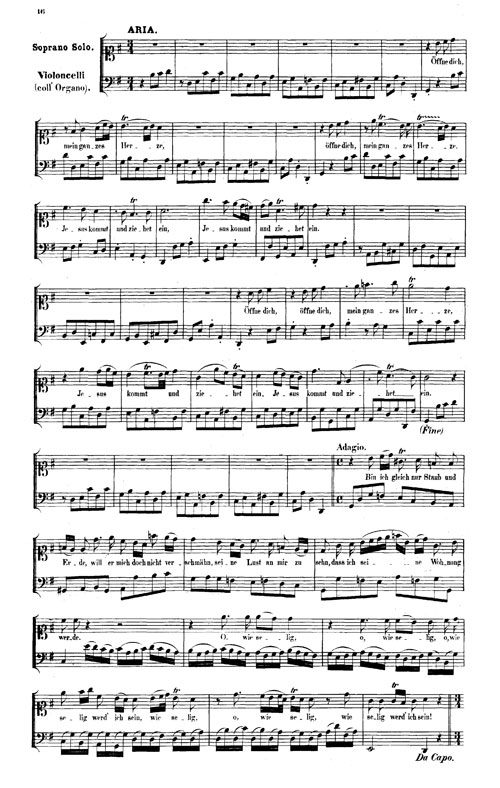

Video Playlist: Bach Arias, but I wrote the obligato parts

January 11, 2022

As some of you know, I started this project near the end of 2020, in October to be exact. My idea was to add obligato instrumental parts to all of Bach's sacred continuo arias (those arias which were written for continuo and voice alone without any additional obligato instruments) with the aim that the new line should sound like it belongs there. The project ended up being 50 arias, though there are more which potentially could have been included. Some arias I didn't work with for various reasons, and there are also more candidates in the secular cantatas which aren't included. In all, the project took about a year, working one day per week. As I write in each of the video descriptions, I did this to learn from Bach's compositions, to challenge myself and improve my skills, and these are all drafts which may be improved. And please note: I wrote only the obligato parts which are marked with an asterisk in the score, J.S. Bach wrote everything else! I used original recordings mostly from John Eliot Gardiner, but also from Philippe Herreweghe, Masaaki Suzuki, Ton Koopman, Kay Johannsen, and others. The obligato tracks were added by me.

Of course, some of my efforts are more successful than others. The important thing for me is that I learned a lot from doing this. I may try some of then again later, or work on some of the secular arias. Lastly, if the embedded playlist above doesn't work for some reason, here is a DIRECT LINK TO THE PLAYLIST .

Happy 2022, and please stay well everyone.

Aaron

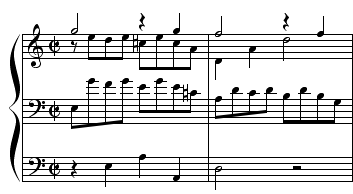

The Equal-Tempered Keyboard, first edition

December 30, 2021

Today is a milestone for me, as the first edition of my book »The Equal-Tempered Keyboard« has finally been published — a collection of microtonal Preludes, Fugues, and Inventions, written (sporadically) over a period of more than 20 years (!) The score is available through Zwillinge Verlag. In 2022 it should also be available on Amazon. Thanks to my friends Patrick Ozzard-Low, Wolf Peuker and Stéphane Delplace for help with editing and translating the preface in English, German, and French, respectively. I'll make a recording of all this music, but that will take some time ...

Cheers,

Aaron

New book — 24 Präludien und Fugen, Band 1, zweite Ausgabe

November 13, 2021

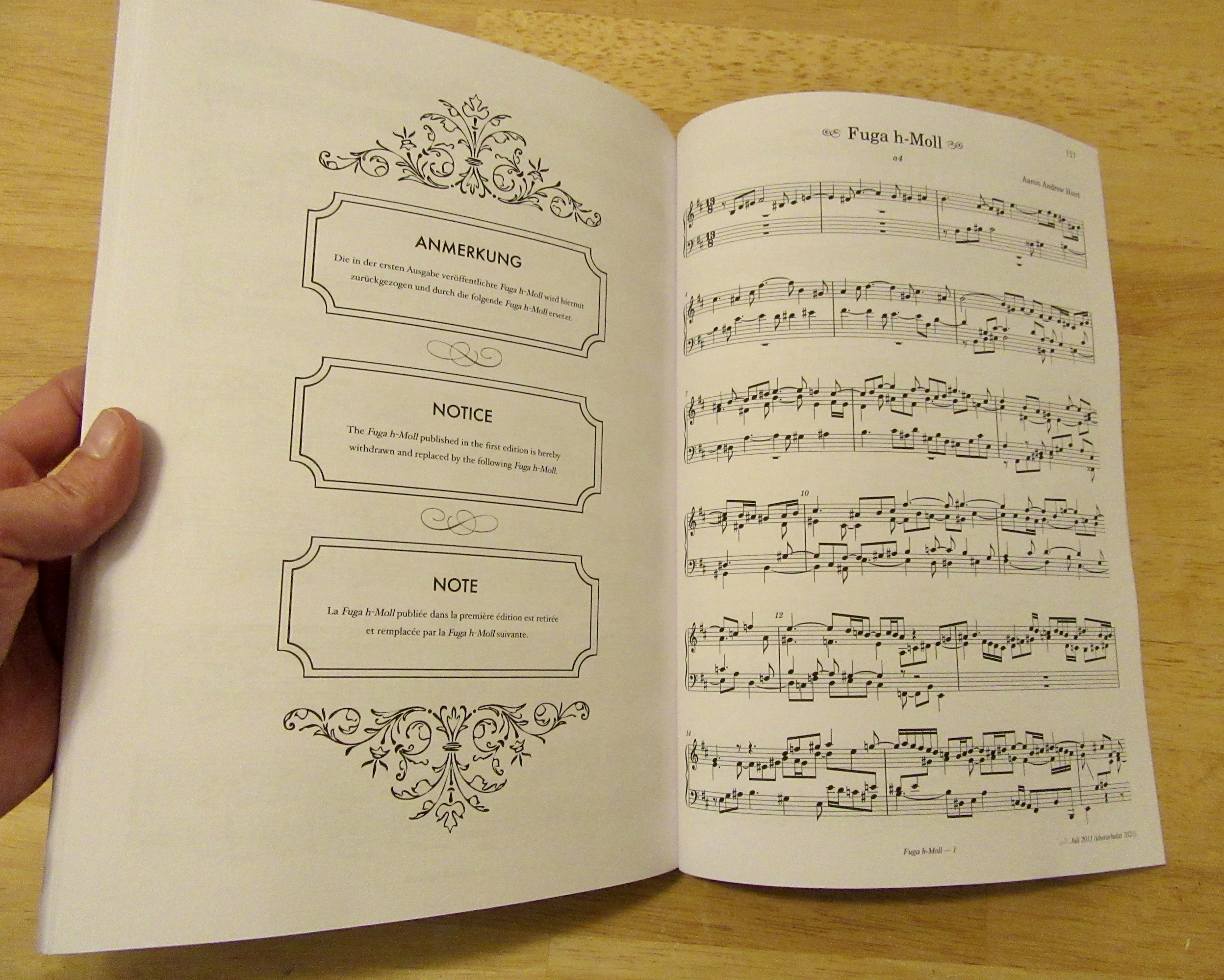

I'm happy to announce the new revised edition of my »24 Präludien und Fugen, Band 1«. A free PDF is on IMSLP and print copies are available from Zwillinge Verlag. This revision took many months to complete. All the errors in the first edition are fixed, the music is improved here and there, extreme care has been taken this time around for things like page turns and proper staff assignments for inner parts, and everything is now playable on a 5 octave harpsichord (FF-f'''), with ossias for instruments of smaller ranges. The book also concludes with a 'new' quadruple fugue in B Minor from 2013 (reworked 2021) which was originally intended to close the cycle. A new preface in English, German, and French explains the details, thanks to my friends Wolf Peuker and Stéphane Delplace for input on the German and French versions respectively.

Cheers,

Aaron

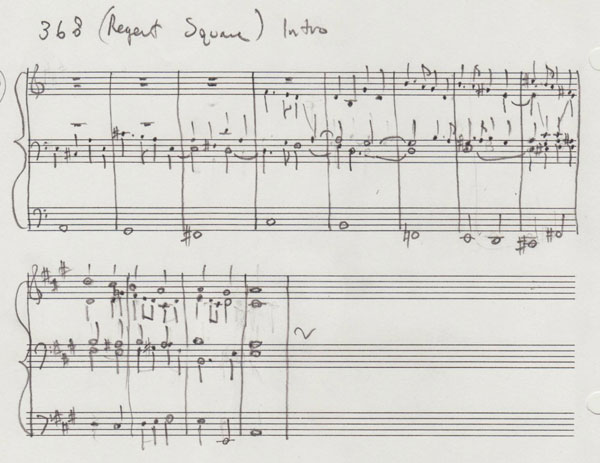

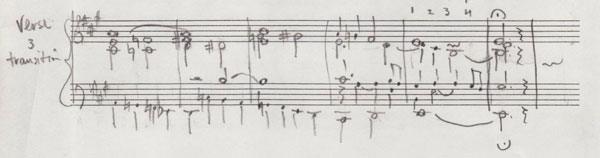

How to make score read-along videos - fast!

March 23, 2021

A couple of years ago I spent some time making YouTube videos of some of my early scores, read-along style. This was a rather painstaking process, involving manuscript scanning or notation tweaking and taking a lot of screenshots, editing images and audio files, and finally putting things together with video editing software. After having done that many times, to be honest I wasn't too keen on doing it again, but after posting a few score images on this blog at the start of my latest project (reimagining Bach's continuo arias), I realised that the best way to share this work would be through YouTube videos.

In the mean time I've also changed my notation software and my video editing software. I felt sure by now there must be a faster way to get results than what I had done before. Sure enough, it turns out these videos can be made in a matter of minutes. I was asked on Facebook how it's done, and I thought the best answer would be to go through the process step by step here.

I assume you have a completed score and a recording of your piece, and a YouTube account. (Making a recording could be topic for another time.) All you need are your notation app and a video editing software capable of uploading to YouTube. I'm using MuseScore and Adobe Premiere Elements, which I can recommend since I know they work well for this, but I assume these steps will transfer to other software.

Begin with your finished score, and follow these steps:

- Copy the source file and rename it Title-VIDEO

- Put that file in a new folder inside your project folder, and name that folder VIDEO

- Set the page dimensions of this new file to 300 mm x 170 mm with 15 mm margins

- Export the score as .PNG at 600 dpi.

The folder is there to hold not only your score but all the supporting files needed to make your video, which (if you're at all like me) you'll want to keep separate from your score since video editors tend to create a lot of subfolders that will otherwise clutter up your workspace. Step 3 makes your score fit the HD screen. It's virtually 16:9 using numbers that are easy to remember, though you can be more exact if you like (302 mm x 170 mm or some other numbers that are in 16:9 proportion). In MuseScore you can do this once and then save the page layout as a Style. Then you just need to use Load Style. The above altogether in MuseScore takes less than a minute for 8-10 page pieces. The most time is taken waiting for the .PNG images to render, so be smart and use that time to set up your video editing app.

Next, in your video editing app, do the following:

- Open an empty project for HD, and save it in the VIDEO folder you made

- Import the images into the project

- Import your audio into the project

- Place the audio on the timeline

- Place the images on the timeline in order, staggered at estimated intervals

- Tweak the placement and duration of the images to match the audio.

- Once the page-turns are all in place, upload to YouTube

Of course here the longest time is spent on the next-to-last step, but once you do a couple of these, you get a sense of where to place things. Premiere has a convenient drag and resize feature that lets you put images side by side and then drag-resize only the left image, and the right image drags along with it, so essentially you're just dragging the page turn point. How long it takes to get all the pages right depends on the length of the piece and how uniform the page turns are. For a work with a consistent tempo where the same number of bars appear on each page, the pages will end up taking equal space. Premiere makes the YouTube upload very easy. Once you allow the app access to your YouTube account, to upload the video you just click a button and type in the info for the video.

A few caveats about the specific software I use - this type of thing will vary based on what apps you are using, but I imagine probably all apps have some quirks you'll have to work around. Adobe could stand to improve their interface for YouTube uploading, as the right-left arrow keys don't work in their input fields (how absurd is that?) The obvious workaround is to type out the info in another app and paste it in. Adobe is also quite lame here as the keyboard shortcut for Paste also doesn't work, but luckily a right mouse click allows pasting. So once you get the hang of it, it's no problem. If you're like me and want to post a lot of similar videos, it helps to have a template for the text anyway. Another small caveat concerning the MuseScore .PNG export is that the files get numbered using suffixes, so you get Title-1.PNG Title-2.PNG etc. which seems fine, except that Premiere doesn't display the full file names after importing, and only shows you thumbnails of the images (which are likely to be totally indistinguishable from each other - imagine viewing the pages of your score at a distance of 50 meters), so after exporting the images, I manually rename the files putting a number at the beginning, so I end up with 1-Title-1.PNG, 2-Title-2.PNG, etc. so that I can see which page is which in Premiere. (Prefixed names should obviously be made an export preference in MuseScore, so I'll be requesting that.)

And that's all there is to it. Here are the few videos I've made so far using this method. You'll notice on the first one I hadn't quite got the HD page size correct, and I had exported the .PNG files at 300 dpi so the image quality is under par. If this helps you make your own score videos, let me know.

Stay well,

Aaron

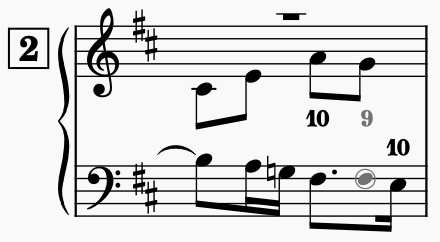

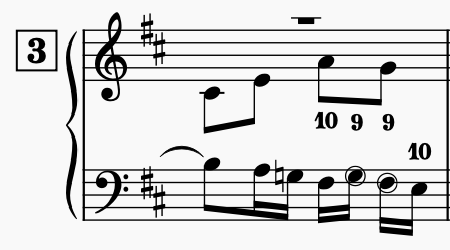

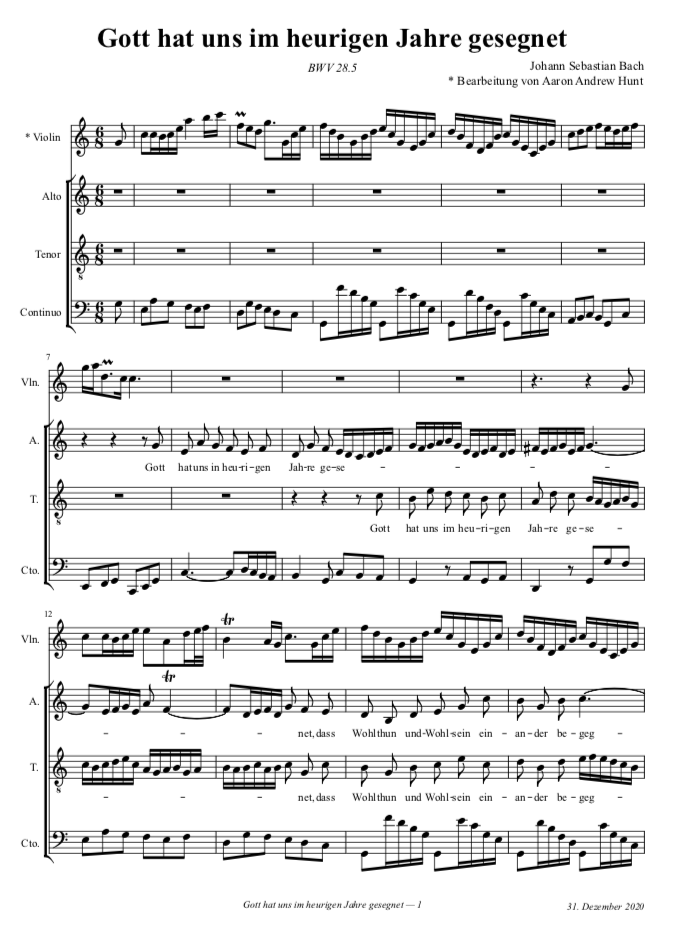

Gott hat uns im heurigen Jahre gesegnet

January 01, 2021

I'm continuing my studies of Bach's continuo arias, adding obligato parts of my own. This week I chose BWV 28.5, "Gott hat uns im heurigen Jahre gesegnet", a duet for Alto and Tenor, from the cantata "Gottlob, nun geht das Jahr zu Ende", appropriate for the new year.

The original recording is from John Eliot Gardiner. The added part is written for violin, but was played here on organ using the Jeux SoundFont.

The text is about being grateful for the blessings of the past year, and trusting for a good year to come.

Gott hat uns im heurigen Jahre gesegnet,

dass Wohlthun und Wohlsein einander begegnet.

Wir loben ihn herzlich und bitten daneben,

er woll' auch ein glückliches Neues-Jahr geben.

Wir hoffen's von seiner harrlichen Güte

und preisen's im Voraus mit dankbar'm Gemüthe.

My translation:

God has blessed us in this year,

so that doing well and being well come together.

We praise him from the heart and ask along with this

that he will also give us a happy New Year.

We hope for this because of his persevering goodness,

and we give praise in advance with a grateful attitude.

I'm sure we can all think of ways this past year has been pretty awful. I for one lost my father to cancer. My friend died of COVID-19. I've been more isolated than ever before in my life. The list could go on. But, let's compare our standards of living to those of 1725, the year this cantata was written, when it was for example common for most children to die of illness within the first few years of life, when common viruses regularly killed otherwise healthy people, and when life expectancy for those who survived was around 50, to say nothing of the undrinkable water, no electricity, etc. In the Western world, and especially in Western Europe, we now have basically the highest standard of living that has ever been achieved on earth. Nevertheless, life can bring us down, mentally, emotionally, physically, spiritually. We are called to remain thankful for our blessings and to persevere with grateful and hopeful hearts. Let's do that.

Amen.

— Aaron

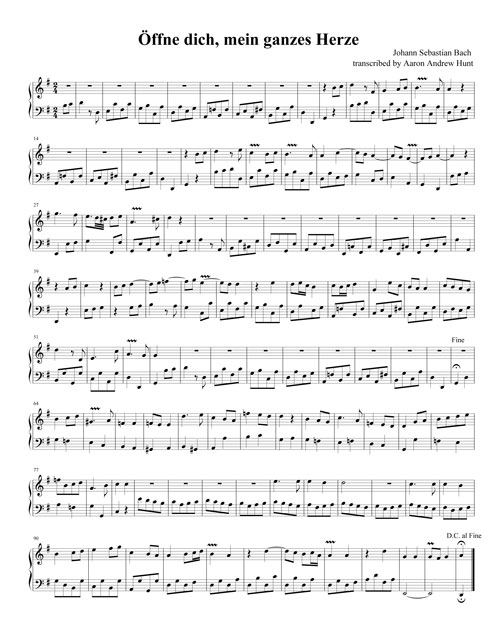

Reimagining Bach's Continuo Arias

December 10, 2020

In his over 200 extant Cantatas, Bach wrote a fair number of Arias for voice and continuo with no obligato instruments. Some of these have figures written in the continuo part, but many do not. Some of these pieces do genuinely sound as if some obligato voice is missing, and in a couple of cases we know a part was lost. Other times it's clear that Bach intentionally chose to write no obligato parts. Listening to performances of these works makes it pretty clear that musicians feel some responsibility to fill these pieces out a bit. Normally the continuo will improvise a lot of filler figures. There may also be double continuo (organ and harpsichord together) to achieve a richer effect. In whatever way the music is performed, there seems to be a general agreement among those playing that, indeed, something is missing here, and there is room to "beef it up" a bit. This room for improvisation makes hearing various performances exciting and interesting.

Over the past few years I've written a few vocal Arias of my own, but have found myself all too often feeling my limits, getting results of varying quality, sometimes clearly subpar. For that reason, all my planned Cantatas remain unfinished. I could just give up, but I decided what I need to do is to study more, and get better. So a few months ago I embarked on a new project, in which I'm given clear direction by the master himself. Every Sunday afternoon I select one of Bach's continuo Arias, copy it in its entirety the way Bach wrote it, and then add my own obligato instrumental part to it. So far I've completed 13 pieces (there are over 60 to choose from). This has been very rewarding so far. it's an excellent way to get into this music and really learn how it's put together, more than I would learn simply by playing through and analysing.

Writing a new line of counterpoint which works along with two existing lines can sometimes be tricky, and at times difficult to choose from many possibilities, but mostly it's easier than composing from scratch. In one sense, this kind of exercise is what continuo players are doing all the time, improvising harmony that goes with the written bass line (and, more often than not, the figures). But writing a solo part is not quite the same as continuo realisation. One of the reasons I thought of doing this project was the fact that very active continuo playing tends to annoy me, because what gets played almost always sounds, well, a bit too improvised. It doesn't have the same kind of thematic coherence as composed music. It sounds at best comparatively less well formed than what is going on around it, at worst disconnected and distracting. The thought occurred to me, that a coherent and purposeful melodic line could do a better job filling in the space.

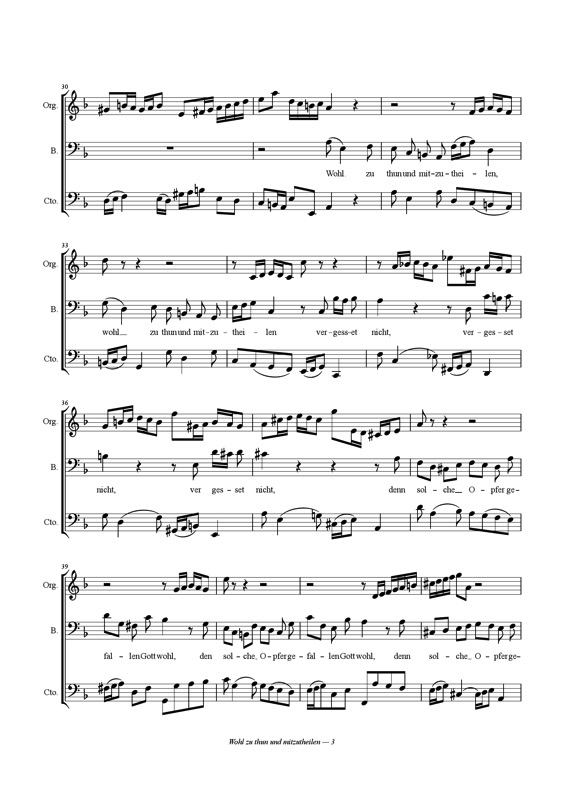

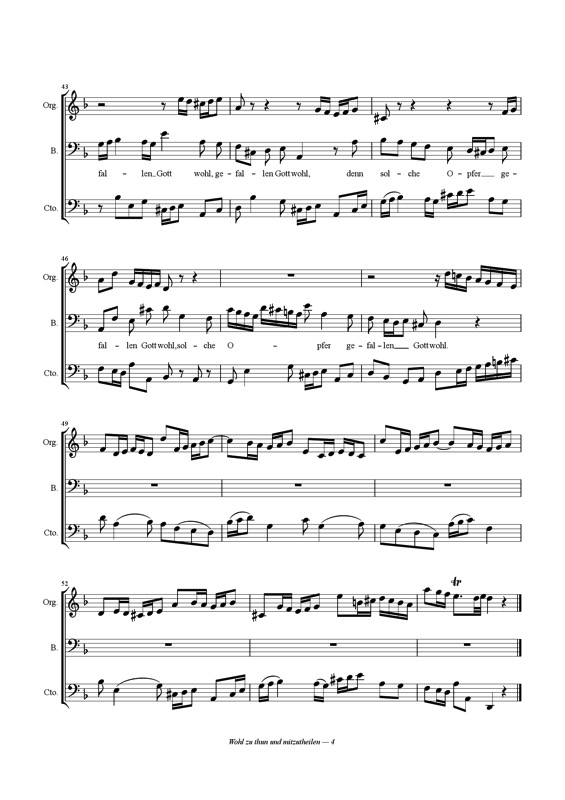

Here's an example to show you what I mean: the continuo Aria for solo Bass, "Wohl zu thun und mitzutheilen" from Cantata BWV 39 "Brich dem Hungrigen dein Brot" The original score does not have an obligato organ part; I wrote the top line, and then played it along with a recorded performance of the work.

The original recording is from John Eliot Gardiner. The added part is played using the Jeux SoundFont. (Although I could use Hauptwerk to get a real sounding organ, the reverb mix unfortunately doesn't work with the recording.) For each piece, I try to add something which sounds like it belongs, like it could have been part of the composition. How closely I reach that goal varies, but my main goal is always reached — namely, that I'm challenged to do and learn something new, by working within existing music that is, without my contribution, already basically perfect.

In the process I'm also finding out a lot about how Bach worked with various texts, which to me are often highly relevant. Take this piece for example:

Wohl zu thun und mitzutheilen,

vergesset nicht,

für solche Opfer gefallen Gott wohl.

My translation:

To do and to share wellness,

don't forget,

for such offerings are pleasing to God.

Which reads a little better in English if we reverse the first two lines and add another word like so:

Don't forget

to do good and to share wellness,

for such offerings are pleasing to God.

Amen.

Stay well,

Aaron

New book — 24 Präludien und Fugen, Band 2

November 21, 2020

In August 2020, I finished writing my second book of 24 Preludes and Fugues. As with any large project, it takes a while after the music itself has been written to proofread everything, make a table of contents, decide on a cover for the book, and so on. The result is now available through Zwillinge Verlag.

Having given the book a final proofreading after its first printing, several minor errors were corrected, and a free PDF is now available on IMSLP.

The Prelude and Fugue in F Minor from this book was made into an animated video by Stephen Malinowski back in February (just after the music was written).

Recordings of the original drafts of most of the pieces have also been published on Soundcloud over the past couple of years, but many finished versions have not yet been recorded. At some point I will release a free recording of all the music on bandcamp.

I feel the book stands well as a collection, and may even show some improvement based on my studies over the past few years. The pieces are all intentionally quite short, intended for all skill levels including intermediate, though some pieces like the fugue in F-Minor are quite challenging to play up to tempo. Many of the fugues are written in only two parts, which makes them of course easier to play, and I think that's a very important quality since keyboard fugues in general have a reputation for being rather difficult to play. There are also many three voice and some four voice fugues, but in contrast to my first book of preludes and fugues which didn't have any particular plan regarding length or difficulty, here I aimed to keep the playability at a reasonable level, and I think that goal was accomplished pretty well.

I do know enough to know for certain that this music is not bad. I'm all too aware that it's never as good as I'd like it to be. Life-long learning hopefully also means life-long improving. I'm happy with this, but God willing, there will be better stuff yet to come. That's the plan, anyway ;)

Please be careful and stay healthy everyone,

Aaron

Konzert in Zeitz

October 20, 2020

In September, my chorale partita "Von Gott will ich nicht lassen" was performed by organist Babett Hartman and soprano Dorothee Mields in the Zeiter Dom, the cathedral made famous by Heinrich Schutz (1585-1672). The concert was recorded and posted on YouTube in two videos, one featuring my piece alone. The concert also got a nice writeup in the Zeitz paper.

Although the partita was written for organ solo, the chorale melody appears in a majority of the movements without ornamentation so that the tune can be sung along with the organ. The idea of singing along was already in my mind as I was writing the partitas in 2018, and it worked so well, I think it may be worthwhile to write out soprano parts for the other partitas as well. If and when I do that, I'll post them on IMSLP (where the score Sechs Choralpartiten can already be downloaded for free).

Stay well everyone,

AAH

How to hide incompetence

August 19, 2019

Let's say you've got good counterpoint chops, but you have trouble sorting out your ideas, and when it comes to form, you struggle. Here's how to cover that up.

- Make it busy.

- Add more ideas.

- Use more techniques.

- Make it long.

Any of these things will draw attention to your strengths and distract listeners away from your weaknesses.

If you need examples of how these tricks work, your hero is Johann Ludwig Krebs (1713-1780). Krebs could have been a great composer, but he wasn't. If only he had had a better teacher… oh, wait, Krebs was a student of Johann Sebastian Bach. In fact, it has been said that Krebs was Bach's best student. Some claim that even Bach himself said this. I think if Bach said this, he was just being polite. Bach had been a friend of Krebs's father, and Krebs jr. also worked for Bach. On the other hand, just because Bach was a great composer, that doesn't mean he was a great teacher. But his students tended to write very good counterpoint, so we guess Bach was a pretty good teacher. It's true that Krebs could write counterpoint very well. But there is a reason not many people today know who Krebs was. The reason is that Krebs was not a very good composer. Sadly, when it comes to his free organ works, he was a pretty bad composer. Why?

Despite his very Bach-like counterpoint, Krebs's music falls short. The main problems are too many unfocused ideas and a sense of timing and form that is all but nonexistent. A sort of mindlessness pervades Krebs's free organ music. Perhaps even worse, there is a sense of "Oh, I can do that too!" If one were to judge his music only by these free organ works, Krebs seems to be an 18th Century "wannabe" composer.

It is instructive to compare the organ music of Krebs to Bach's organ music. One can learn some things this way about what makes Bach's music so good. On the surface, Krebs's counterpoint often looks like Bach's, but important things are missing - things like reason, coherence, and purpose. Krebs's work is sort of like what artificial intelligence might be able to produce from studying Bach. AI produces brainless output. It has no mind and no soul. That is what Krebs's free organ music tends to sound like. Sometimes Krebs simply stole directly from Bach (which is incidentally something attempts at AI-Bach composition also have done). For example, in Krebs organ Toccata in a-Moll (Krebs-WV 411), there are a few bars which are suspiciously similar to Bach's Toccata in F-Dur BWV540. Listen and compare:

Krebs-WV411

Bach BWV540

Notice the pitch levels are even the same. This is not really so surprising, since we know that Krebs copied Bach's organ scores by hand (in fact many of Bach's works were preserved only as hand copies from Krebs!) Listen to a little more of both works, and the difference in quality between them is not hard to miss. Where Bach used a strong idea and worked it out brilliantly with perfect timing, Krebs simply stole the idea and dropped it into his music with no rhyme or reason. The idea appears briefly and has basically no relation to anything around it. Krebs even oversteps a very basic guideline and pushes the stolen sequence one step further than Bach did. Then music just keeps plodding on and on, for no real reason. There are numerous other instances of this kind of thievery. In this even more appalling example, Krebs lifted a sequence almost note for note out of Bach's Die Kunst der Fuga (The Art of Fugue).

Krebs Partita in B-Flat

Bach BWV 1080

Again, the pitch levels are the same. Conicidence? Not likely. (By the way, I've never seen anyone else point these things out.) That J.L.Krebs obviously had his mitts on The Art of Fugue seems like something musicologists should be looking into. Maybe they have and I just never heard about it. I suppose it's possible that Krebs slipped in these little quotes from his teacher on purpose as jokes, in order to get a rise out of Bach. But I don't get the sense that Krebs wanted his music to be funny. Or maybe these really are Krebs's ideas, gems amidst the chaos, and Bach cherry-picked them from Krebs to develop in his own music … and maybe unicorns exist.

Besides writing good counterpoint, technically speaking, what Bach was able to do better than anyone else was to tell a good story. In Bach's music, the technique alone is not only solid, and the ideas are not only strong, but the form is also balanced, the timing is right on, the drama is effective, and the feeling is authentic. In a good story, we care about what happens, we find meaning, we are moved emotionally, and by the end of the story, we feel a sense of catharsis. How that is done is not easy to understand or explain. But that's what Bach was able to achieve with his music, and that's what distinguishes his music from mere counterpoint.

Though Krebs fell short of being able to tell a good story, we can be grateful to him for teaching us thereby that writing good counterpoint, though it is a good start, is not enough. Not nearly enough! So far, Artificial Intelligence (which in fact means brainlessness and soullessness) teaches us something similar.

Maybe you have figured out by now that the tricks listed above don't actually work. When the music is busy, has lots of things in it, and is long, and technically dense, that is very likely to be a bad piece of music, where no coherent story is being told. Instead, it's similar to someone babbling. Babies babble. Most of us did this in our infancy. It was entertaining, for a while. It's how most of us learned to talk. As we get older, we have a choice to make: to continue to babble forever, using distraction to get by, or to grow up and get to work on telling good stories.

Best Regards,

Aaron

New album released - Sechs Choralpartiten

May 07, 2019

I've released a (free) recording on bandcamp of my work over the last year, composing an average of about 1.5 days a week, The German title "Sechs Choralpartoten" means "Six Chorale Partitas" in English. 61 tracks add up to a little over 2 hours of music as follows.

- Alle Menschen müssen sterben (27 min.)

- Von Gott will ich nicht lassen (19 min.)

- Straf mich nicht in deinem Zorn (26 min.)

- Ich steh an deiner Krippen hier (12 min.)

- Das alte Jahr vergangen ist (8 min.)

- O Mensch, bewein dein Sünde groß (78 min.)

The full track list, full text and some comments are on bandcamp. The organ is the beautiful OrganArt Media Vollenhove Bosch-Schnitger, a brilliantly done sample set.

This project started in April 2018 and lasted until the end of April 2019. The scores will also be published later this year. are published as free PDF download on IMSLP and in print copy by Zwillinge Verlag.

Regards,

Aaron

O Mensch, bewein dein Sünde groß

February 19, 2019

Almost a year has passed since my last post here, in April 2018. Needless to say, a lot has happened. I won't try to summarise. Instead we simply pick up the thread today.

Later this year I'll be publishing a collection of six chorale partitas for organ (a few hours of music). This setting of O Mensch, bewein dein Sünde groß is my most recent work. The melody is by Matthias Greitter, 1525. The text is a retelling of the Passion of Christ in 23 strophes, written by Sebald Heyden in 1530. Only the first and last strophes are used in the modern Gesangbuch, so that very few people know that the other 21 strophes even exist. I've chosen to set all 23 strophes, which presents some interesting challenges. The tune itself is not short. In fact it is so long that it may seem like questionable aesthetic judgment to set the melody 23 times for organ. This is why I am using many techniques to ensure that the material remains engaging throughout. For example, this piece is a setting of not one but four strophes. The texts are set in two canons, each led by the tenor voice. The answering voice of the first canon is hidden in the soprano in inversion at a very short distance (one beat, and even closer in a couple of phrases). The second canon is easier to hear, between the tenor and the pedal, with the melody upside down in both parts, in the minor mode.

Regards,

Aaron

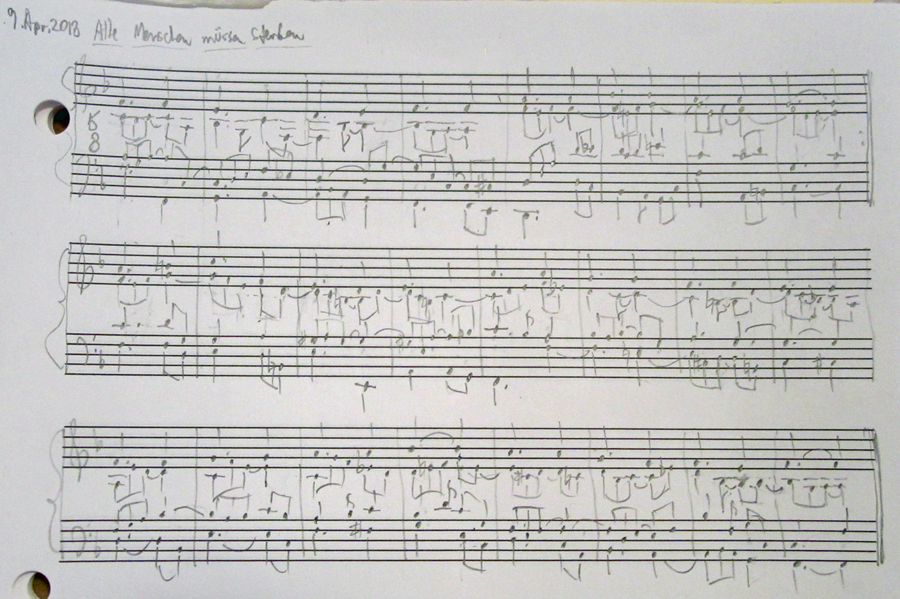

Alle Menschen müssen sterben

April 09, 2018

My setting of the great Chorale by Johann Georg Albinus (1652) [alternately attributed to Johannes Rosenmuller (1620-1684)]. I chose a meter of 5/8 because the number 5 is associated with mankind (fingers on a hand = 5, toes on a foot = 5, 2 arms + 2 legs + 1 head = 5, primary senses = 5, and so on). This tune is usually pitched in A or G. I chose the key of F because of another project I'm working on, in which I want to include this melody in F.

The performance was recorded using Hauptwerk, with the Bosch-Schnitger Vollenhove organ from OrganArt, which is pitched at 419.4 Hz.

Regards,

Aaron

N.b. I forgot to write a few dots on some of the quarter notes. Can you find the missing dots?

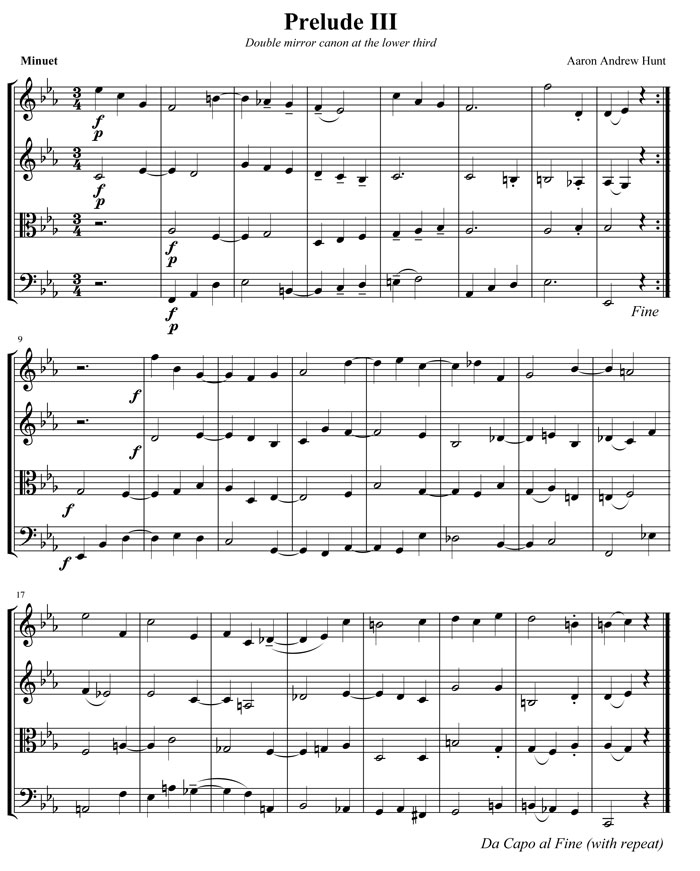

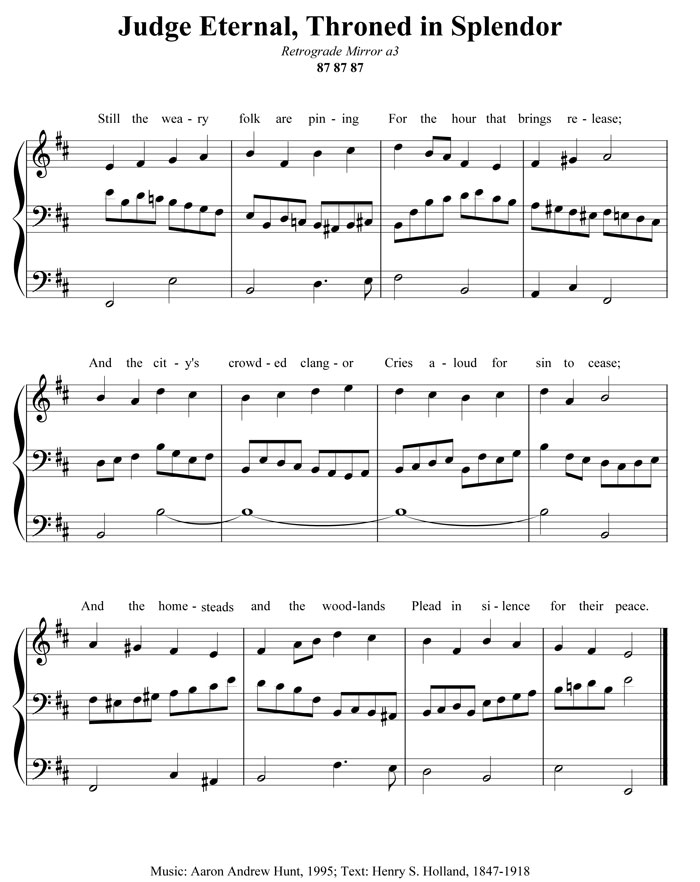

2 new books available - Previews

August 06, 2017

My devoted blog-followers (yes, both of you) will recall that I've been working on a new book for publication. I'm happy to announce that Suite of Mirror Canons in C and Treatise on Canonic Inversion with collected works demonstrating mirror canons, is finished. Weighing in at 163 pages, it includes a 47-page treatise, 7 Double mirror canons for string quartet, 7 mirror canons for keyboard, and over 30 additional works based on mirror canons for various instruments, written between 1995 and 1997. A live recording of the Suite is also available for download, with previews at the Zwillinge website. Below is a preview from the book, one of the double canons for string quartet, with audio. Click the image to download a PDF.

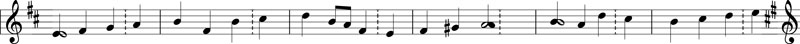

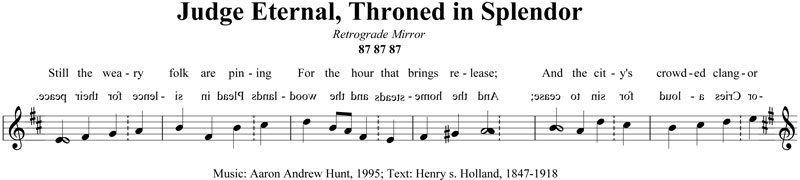

Check out the book at Zwillinge.

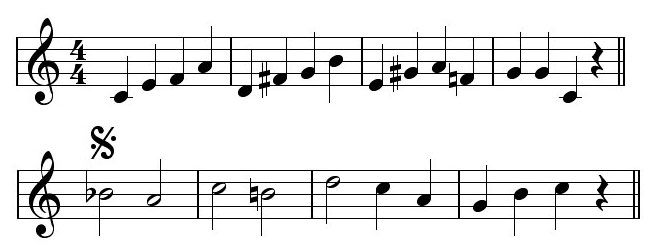

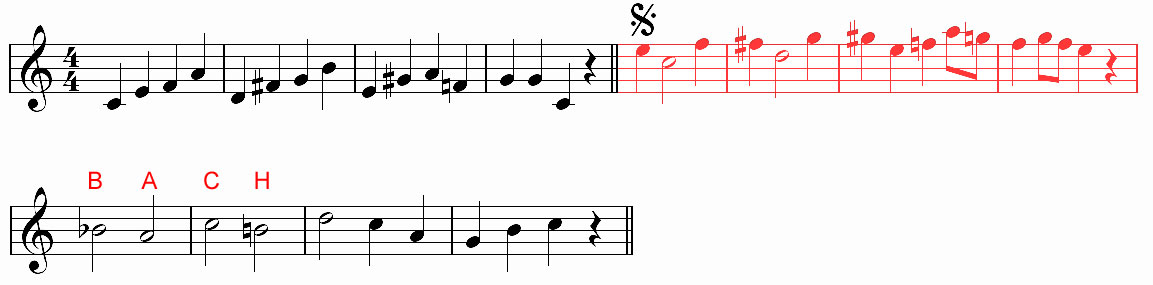

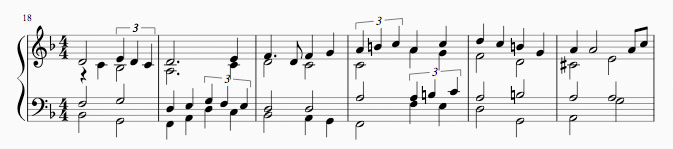

As I was preparing the additional material for that book, I realised that several of the more substantial works would be better off published in a separate volume. The result is the 123-page 32 Sacred Canonic Choral Works. This collection contains works based on direct canons as well as mirror canons. Many of the pieces come from a collection of Canonic Hymns and Preludes, written in 1994-95. For that project, I chose texts from the Lutheran Hymnal. Each text was set to a canonic melody, and at least two works were written, one a conventional four-part hymnal harmonisation, and the other a canonic realisation. Each set of works could also include one or more preludes for organ, implementing the canonic tunes in different ways. For example, the tune I composed for Judge Eternal, Throned in Splendor is a canon at the octave with a symmetrical mirror retrograde form. A 3-voice setting is shown below, with audio. Click the image to download a PDF.

This tune can be written as a puzzle canon in several ways. Here's one option. When you get to the end of the line, turn around and read backwards, following the dotted barlines and the mirrored note values.

With the text added, it looks like this:

Check out the book at Zwillinge.

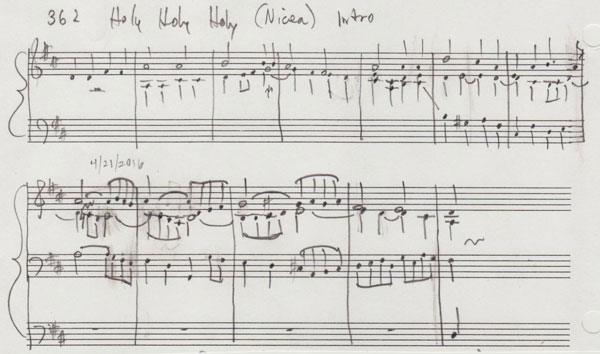

A third book of my earlier music is also on the horizon. It will be a collection of 17 Festival Hymns for choir, organ, 2 trumpets, 2 trombones, and timpani, from the years between 1999 and 2002.

Regards,

Aaron

Festtag!

July 20, 2017

Heute ist für mich ein Festtag, denn ich wohne jetzt seit einem Jahr in Deutschland. Mein Deutsch ist immer noch ein bisschen schräg, aber es hat sich seit meiner Ankunft viel verbessert. Deshalb schreibe ich jetzt meinen ersten Blog-Vermerk auf Deutsch. Na ja, ich mache das nur ganz kurz. Natürlich würde es besser sein, mein Blog weiter auf Englisch fortzuführen. Gut, dann das mache ich jetzt. Übrigens, falls Sie Deutscher sind, und ein bisschen Zeit für mich haben, können Sie meine Fehler gerne korrigieren. Das wäre toll. Vielen Dank!

For those of you who don't read German, what I tried to write above goes something like this in English: Today is a special day for me, because I have now lived for one year in Germany. My German is still a little odd, but it has improved a lot since my arrival; therefore, I'm writing my first blog entry in German. Well, I'll keep it short. Of course, it would be better to continue my blog in English. Good, I'll do that now. By the way, if you happen to be German, and you have a little time for me, please correct my mistakes. That would be great. Many thanks!

Regards,

Aaron